A Long Obedience

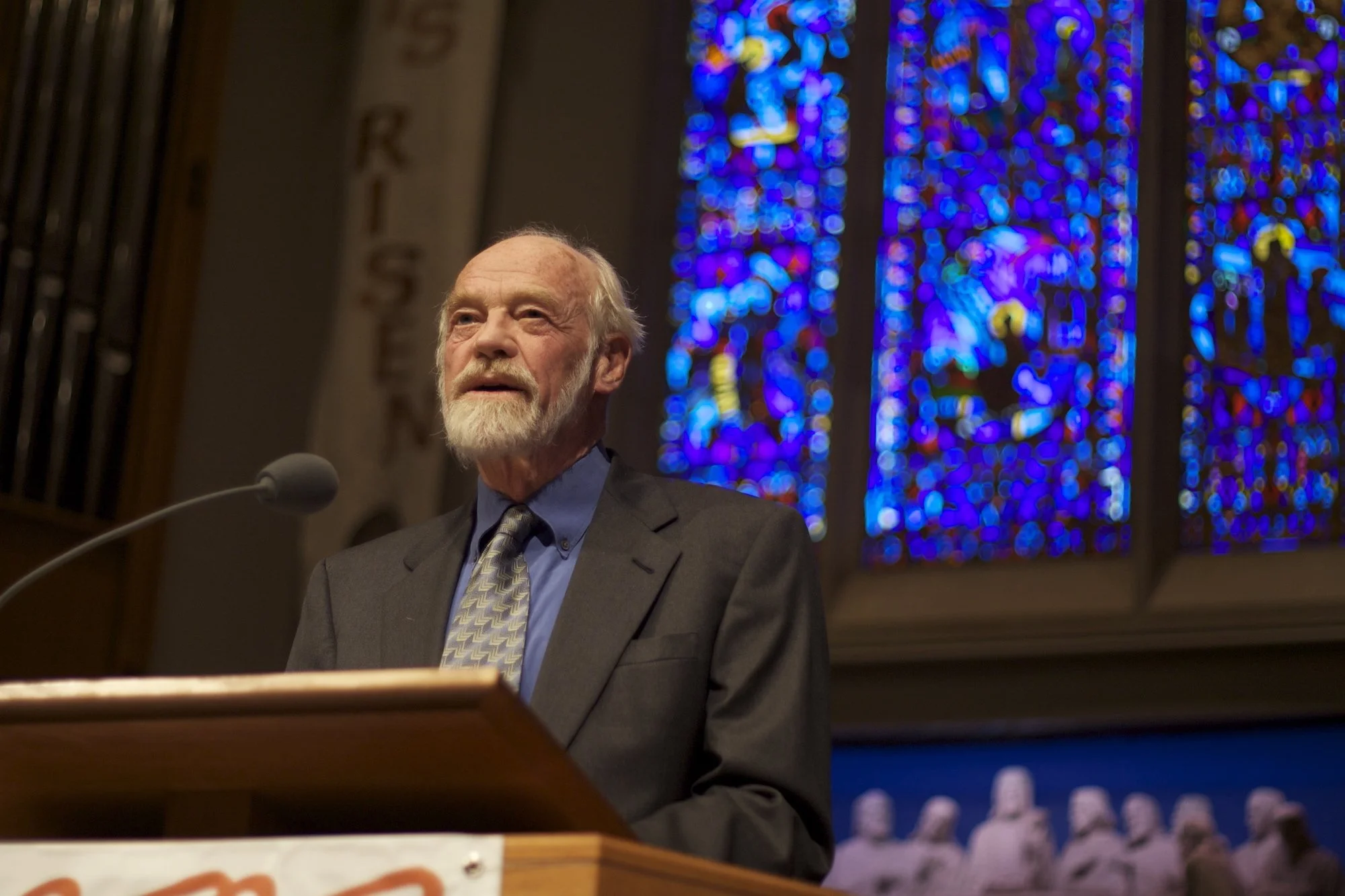

It’s been moving to read all the tributes to Eugene Peterson, the beloved author and pastor who died early last week at the age of 85. The bestselling author of The Message translation of the Bible, Peterson also wrote dozens of books about theology and the life of faith. His funeral will be held today in Kalispell, Montana.

Peterson didn’t write the first of his books until he was 48 years old, a move that strikes me as remarkably wise. For 29 years, both before and after his publishing success, he served as the pastor of a modest Presbyterian church in Maryland. This is the role that continued to define his sense of calling until the end of his life. Indeed, when he published a memoir in 2011, it was simply called The Pastor.

Long considered a pastor to pastors, Peterson was also a tremendous encouragement to laypeople near and far. As this post from the Laity Lodge retreat center in Texas put it, “Eugene was a longtime friend and ally in recovering the sacred identity of the laity.” Count me among those grateful for this much-needed recovery.

There were always Eugene Peterson books on the shelves growing up, but to my shame, I didn’t read any of his work until my twenties. As a small group leader at Urbana 03, I was given a copy of A Long Obedience in the Same Direction, a book about discipleship based on the Songs of Ascent in the Psalms. I’d like to say I savored it, but “devour” is probably closer to the truth. I’ve been “eating” (and re-eating?) his books ever since.

Eugene Peterson has taught me at least two key things. First, he showed me the spiritual importance of being embodied in a particular place. Whereas there’s always a gnostic temptation in church circles to overly spiritualize everything, Peterson insisted on keeping his feet – and ours – firmly planted on solid ground.

Possibly the most-quoted verse from The Message is Peterson’s translation of John 1:14: “The Word became flesh and blood, and moved into the neighborhood” (emphasis mine). In the foreword to a wonderful book on placemaking, he wrote, “I find that cultivating a sense of place as the exclusive and irreplaceable setting for following Jesus is even more difficult than persuading men and women of the truth of the message of Jesus.” Those words, perhaps more than any others he ever wrote, have haunted me for over a decade. I think of them and wrestle with the implications often.

The other significant thing Peterson has done for me is to open my eyes to the beauty and brutal honesty of the Psalms. Bono and I have that in common, it seems.

“We need to find a way to cuss without cussing,” Peterson has said, “and the imprecatory Psalms surely do that.” Not only do the Psalms give us words to express our disappointment with God, our questions and our rage, they also give us the language we need to express wonder and hope. Eugene Peterson was a man who immersed himself in the psalter, and it showed.

At some point along the way, I discovered that the H in his name stood for Hoiland. This, for obvious reasons, intrigued me. Years later, in his memoir, I learned perhaps more than I ever cared to know about our shared family tree: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

I never had the chance to meet Eugene Peterson, but I already miss him. Like so many others, today I’m thanking God for his life.