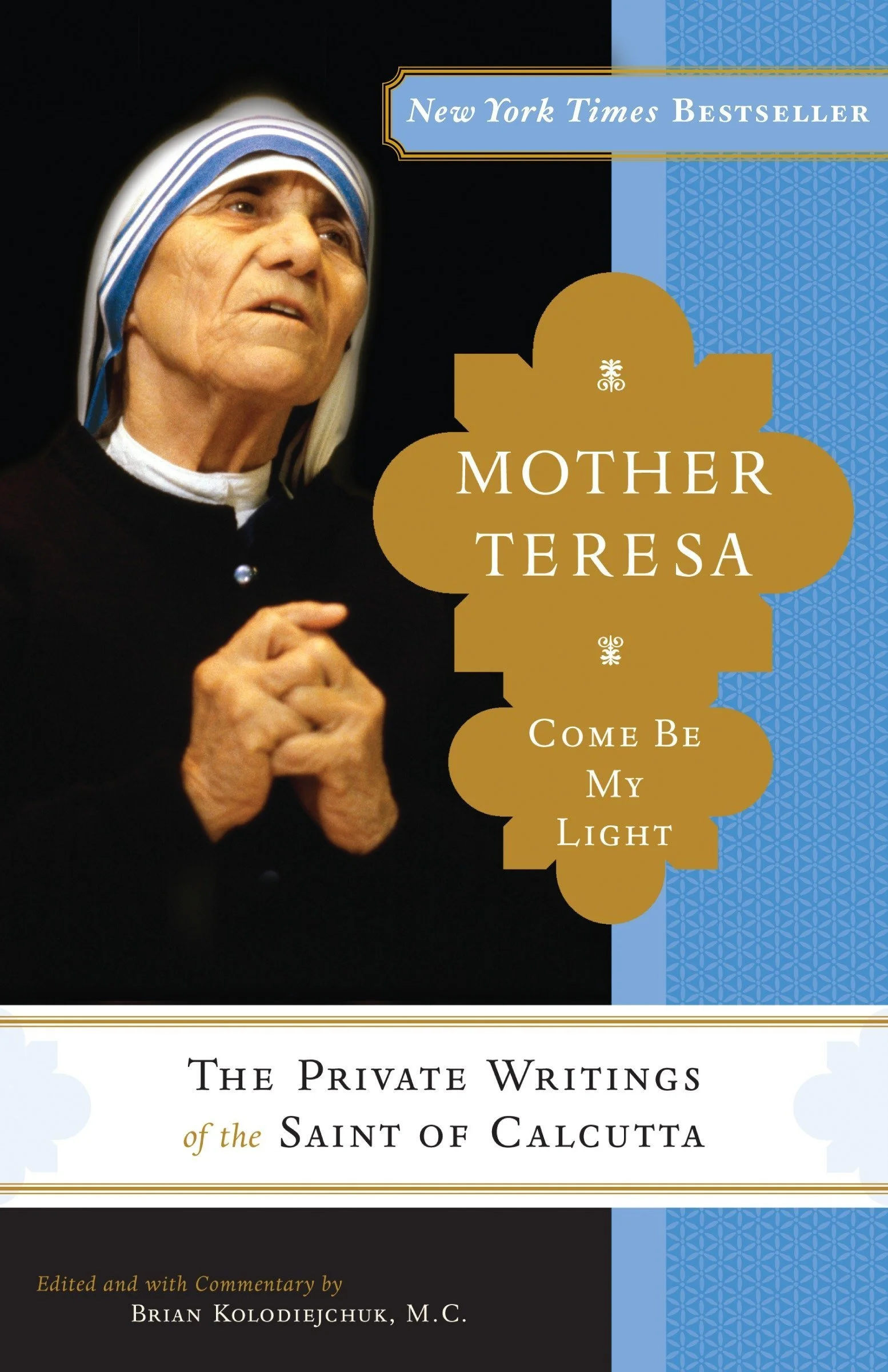

Mother Teresa: Come Be My Light

I admire Mother Teresa. But I am deeply ambivalent about Come Be My Light (Image), the collection of her “private writings” edited by Brian Kolodiejchuk. I’m conflicted in ways I didn’t expect to be.

There’s no doubt that Mother Teresa was a holy woman, as well as a force to be reckoned with. The broad contours of her life and public ministry are well known, especially the awe-inspiring work of the Sisters of Charity among impoverished and dying persons in Calcutta. But in this book, which has been in circulation for many years now, we also get a glimpse of her hidden faithfulness amidst extraordinary hardship—namely, a decades-long spiritual desolation she did not understand and could never escape.

This book, which was published posthumously, consists of hundreds of Mother Teresa’s letters to her bishops, priests, and spiritual directors—letters she explicitly and repeatedly asked to be destroyed. In other words: you and I were never supposed to read them. So yeah, that’s problematic from a publishing standpoint. But at an even deeper level there’s the underlying and unwavering commitment of Mother Teresa to keep anyone but a select few superiors from understanding the reality of her spiritual life. Not only were these letters never intended to be made public; Mother Teresa never let the nuns in her care know that behind the joyful, serene facade was a persistent, soul-crushing dark night of the soul.

It’s one thing, surely, for a spiritual leader to refrain from burdening his or her people with every inner struggle in great specificity. There’s wisdom and true pastoral care involved in that kind of restraint, and I can appreciate this as yet another of the crosses that faithful spiritual leaders must be willing to carry. But leaders should lead from their struggles, should they not, trusting that God will use their faithful wrestling and stumbling for some good purpose in the lives of others?

Mother Teresa would not have been the only Sister of Charity who struggled to hear the voice of God, to feel his presence, to experience his peace. (She is not the only one of us, for that matter, who has found it nearly impossible, at times, to find any words at all to pray.) Other nuns in her order, women unknown to history, must have routinely felt just as hopeless as Mother Teresa did. And as they tended the wounds of the sick and sat in silence with the dying, they would have felt utterly alone in their desolation. They must have felt less spiritually alive than Mother Teresa, less worthy of God’s favor. Needlessly so, in my estimation.

Because what we see in these letters is Mother Teresa’s insistence on never acknowledging this reality to the people who needed, most of all, to know they were not alone. One of the women who joined the Sisters of Charity in the early days is quoted as saying, “Mother was a very balanced person and Mother was joyful when things went right; but even when things went wrong, she would not show depression or moodiness. In season and out of season she was joyful” (p. 188). Not only was she committed to demonstrating this kind of perpetual strength near and far, she also insisted on her sisters doing the same. In a short corrective letter to a nun she writes, “I was very sad to see you this morning so down & sad . . . Be good, be holy—pull yourself [up]. Don’t let the devil have the best from you . . . Just be cheerful” (p. 189).

I’ll be honest: I distrust “joyful” Christian leaders who are unable to cry when tears are called for, who are not conversant in the language of lament. I have compassion for these people, I do, but I don’t consider them spiritually or emotionally praiseworthy, let alone instructive. Denying the reality of the darkness is not the way of Jesus, who did not hide his tears in public situations of sadness. Nor is it the way of the psalmist, who writes with the recognition that so much of the life of faith will be lived in the valley of the shadow.

Mother Teresa’s ministry was a long obedience in the same direction. Her life is an encouragement and a challenge to me, and I thank God for her witness. These revelations of her long inner turmoil don’t compromise any of that; instead, they actually make this saint relatable. That’s why, in this insistence on burying the truth about her dark night of the soul, and in preventing her sisters from being honest about their own spiritual struggles, I believe she did them a disservice. And when the spiritual leaders in our own lives insist on a flimsy mirage of positivity, they do us a disservice as well.