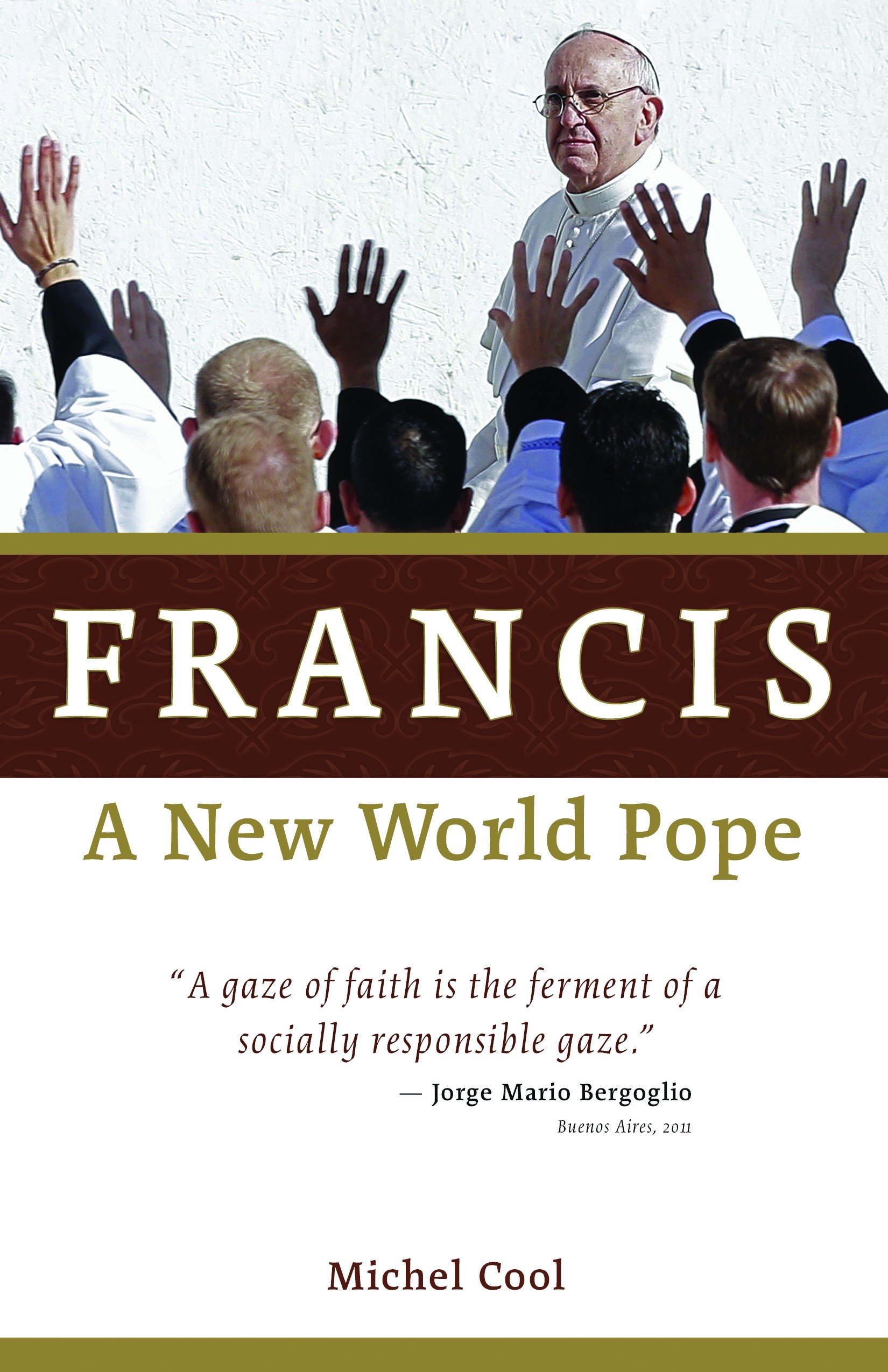

Francis: A New World Pope

Ever since Jorge Mario Bergoglio was elected by the papal conclave this past March, becoming the 266th pontiff and the first to take the name Francis, it seems the whole world has been abuzz with prognostications about what new directions the Catholic Church will take with the “People’s Pope” at the helm.

Indeed, from the moment he first appeared on the balcony at St. Peter’s it became clear that Pope Francis was serious about trying to live up to his medieval namesake. Notably absent was the regal dress of his predecessor, Pope Benedict XVI. And before he blessed the people, he instituted a powerful reversal by asking the people to pray for him.

As stories about the life of the new Bishop of Rome started to emerge, we saw that while these demonstrations of humility and simplicity may have broken with tradition for the papacy, they were nothing new for the former Archbishop of Buenos Aires. For years he had regularly visited the poor and the outcasts in his native Argentina, taking public transportation and walking through mud to get there. And just as he seemed determined to do in the Vatican, he had lived for many years in a relatively austere apartment. With “street cred” like this, the buzz surrounding Pope Francis has been understandable.

In his slim new book Francis: A New World Pope, French journalist and religion writer Michel Cool paints a portrait of Bergoglio’s path to the papacy and seeks to put the election of the new Pope into perspective.

As Cool demonstrates, Francis is seen by many as an outsider, and in important ways, he is. There has never previously been a Pope from the so-called “New World” and never before has the Pope been a Jesuit. Accompanying these unprecedented changes, some critics of the Vatican’s perceived stodginess hope he will bring sweeping changes, not just in style, but also in doctrine. Catholic faithful who recognize the Vatican’s failures and grieve over the recent sex abuse scandal, meanwhile, hope Francis will restore the Church to health and respectability.

Commentators have latched onto sound-bytes from Francis’s surprisingly candid interviews in which he has said, for example, that the Church can no longer be “obsessed” with the issues of abortion and same-sex marriage. Some of those commentators have, however, conveniently ignored his statements affirming the Church’s long-held teachings on these matters. For those outside the Church, the Pope’s seemingly contradictory comments have been vexing, but needlessly so, in my opinion.

What confounds so many about Pope Francis, it seems to me, is precisely the consistency of his Catholic views. Catholic social teaching has long affirmed the importance of caring for the poor and oppressed, something Pope Francis clearly demonstrates. The Church has also been dogmatic in its opposition to abortion, a position Francis holds firmly as well. Both convictions stem from the belief that all people—rich and poor, born and unborn—are created in the image of God and are therefore worthy of dignity, respect, and care. Yet holding these twin convictions with integrity makes it difficult for the press to decide whether the new Pope is liberal or conservative, the polarizing (and often unhelpful) terms used to categorize people in society at large.

Cool’s description of Francis as a “new world” Pope refers, of course, to the fact that he is from the Americas, as opposed to the “old world” of Europe. But the term also seems to poignantly represent the reality that Christianity is expanding most rapidly in the Global South, a phenomenon that is reshaping both Protestant and Catholic churches alike. It is significant that the Catholic Church now looks to a representative of the Global South for spiritual direction. Those of us belonging to Protestant traditions would do well to likewise consider who our Global South leaders and teachers might be.

If this book’s greatest strength is its warm accessibility, its greatest weakness is that it’s quite disjointed. Each chapter can more or less stand on its own, and less than half the book is actually written by Cool himself (though his brevity is understandable given how quickly after the Pope’s election it has appeared). The rest of the book consists of excerpts from Francis’s sermons and writings, and reflections from a dozen or so Catholics who express their fervent hopes for his papacy.

In a chapter on ten hot button issues Pope Francis will need to address, ranging from moral crises to interfaith dialogue to economic concerns, I was reminded of the moment in which St. Francis of Assisi discerned his calling. As the story goes, Jesus told him, “Francis, go and rebuild my Church, which you can see has fallen into ruin.” Francesco immediately set about dirtying his hands with bricks and mortar, but eventually it became clear that rebuilding the church would in fact mean getting to work with “living stones”—the people of God.

Pope Francis seems to recognize this, as his spur-of-the-moment phone calls to single mothers and his washing of the feet of addicts make clear. One need not belong to the Roman Catholic Church to share in the hope that his efforts to rebuild the Church will be fruitful. But in the words of Belgian priest and writer Father Gabriel Ringlet, quoted near the end of the book, “Let’s give him a little time to show us what he’s going to do.”

This review originally appeared in The Englewood Review of Books.