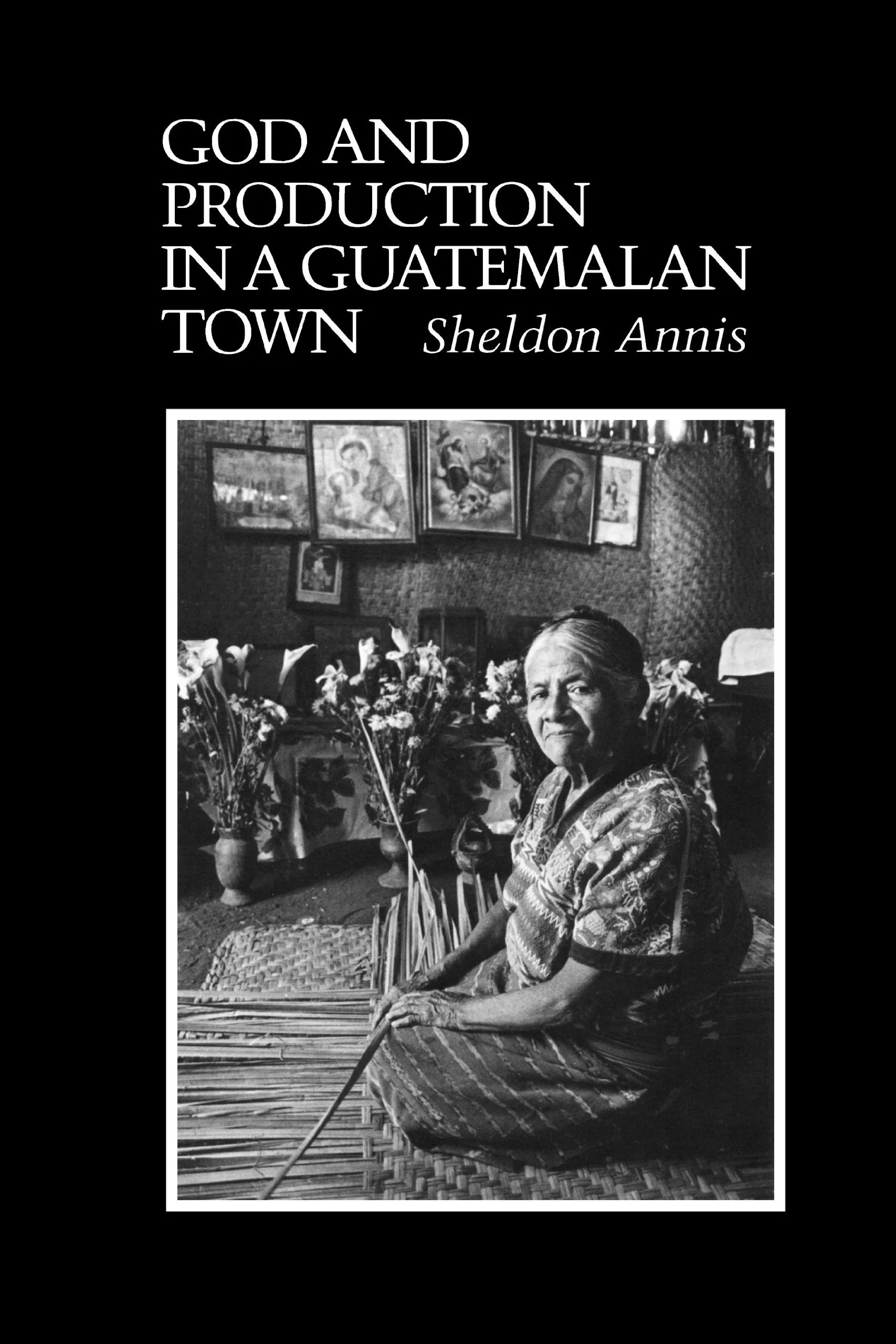

God and Production in a Guatemalan Town

While in Portland for a conference earlier this year, Katie and I got to visit the famed Powell’s Books, along with our friend Elise. We had a ridiculously tiny window of about 30 minutes to explore the place between conference sessions, while it would take a full day or two to do the place justice. Nonetheless, I split my time between the Religion and Latin America sections (no surprise, right?). I ended up buying a book dealing with both.

God and Production in a Guatemalan Town (University of Texas Press) was written by Sheldon Annis 25 years ago, and focuses on the rise of Protestantism in Guatemala by honing in on social and economic trends in San Antonio Aguas Calientes, a small village near Antigua, a big tourist town in Guatemala.

There’s a lot less God than production in the book’s pages. The author himself concedes as much, but I was disappointed with that lopsidedness nonetheless. Throughout the book Annis attributes the rise in Protestantism largely to economic, social, and political trends in the country during the mid-80s. Only at the end does he concede that there may be more going on than meets the researcher’s eye when it comes to dramatic shifts in religious belief and practice. I think Catholics and Protestants alike would agree that their deeply held beliefs aren’t explainable in merely socio-economic terms. Nonetheless, for those who are accustomed to exploring how religion shapes culture (or how it ought to shape it), it’s helpful to consider how culture possibly shapes religion as well.

German sociologist Max Weber famously argued that a “Protestant work ethic” lay behind the rise of capitalism and the rapid creation of wealth in the West, and Annis draws on this argument when he explores the simultaneous rise of Protestantism and changes in economic activity in San Antonio. He suggests that the typical village in Guatemala has found its identity largely in Catholicism and its sense of “Indianness,” both remnants of the country’s colonial past. Additionally, the traditional village revolves around the milpa, a small plot of land used for growing corn and beans. This system is reliable for subsistence farming and it contributes to a sense of community harmony, but it doesn’t really work for economic growth. As milpas become overcrowded, those on the margins find themselves rethinking traditions and considering new ways of life.

It is here, in Annis’s view, that Protestantism finds an opening. While most Protestants begin from a place of social exclusion and economic hardship, many become entrepreneurial and end up doing comparatively well for themselves. Having left behind the “milpa logic” of their Catholic neighbors, Annis says, Protestants now embrace a very different “rags to riches” sort of logic, not unlike Weber’s analysis.

Though the findings of this book are by now a bit dated, I find all of this to be especially important and timely food for thought for Christians, whether Protestant or Catholic, who are working in the field of development. Several big questions come to mind.

What’s gained when shifts like these take place? Equally important, what’s lost? Is economic growth the absolute goal, trumping all other values including the “community harmony” represented in the more traditional way of life? Could there be a way to preserve traditional values alongside economic growth? How do we understand the connection between faith and development? Does one explain the other? Is the relationship symbiotic?

Our answers to these important questions hinge on our definition of development and our vision of “the good life.” And as Christians, we can’t define these things apart from our understanding of who God is, how he relates to the world, and how he calls us to respond.

Ultimately, of course, outsiders can’t be the ones to determine how those in villages in San Antonio will live. The men and women of San Antonio must be the ones to make their own decisions because they will be the ones left to live with the outcomes.

Yet this book serves as a reminder of something crucial: Christian development practitioners must be able to think theologically about their work, even while affirming the central role of community residents in shaping their own future, lest we contribute not to the community’s development, but to its eventual ruin.