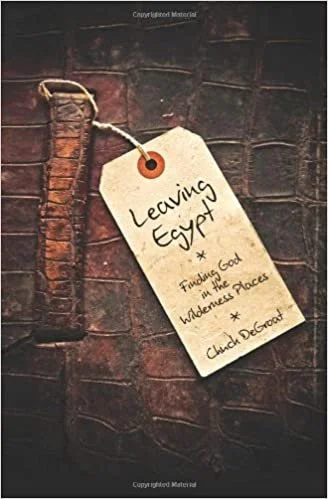

Leaving Egypt

Before it is anything else, the story told in the book of Exodus is a story of God acting in history to free his people from captivity in Egypt. It’s a story of God’s faithfulness to a not-so-faithful people.

In that story, however – that true story – there are lessons to be learned for those of us who have never been made to make literal bricks in a literal Egypt. Dr. Chuck DeGroat, author of Leaving Egypt: Finding God in the Wilderness Places (Square Inch), writes in the book’s introduction, “I have come to believe that the Exodus story deeply reflects all our stories.”

Drawing on his experience as a pastor and therapist in San Francisco, DeGroat meditates on the ways in which the journey out of Egypt and the journey out of addictions have powerful parallels, giving us helpful language with which to speak about enslavements of various kinds and the pervasive guilt and shame that accompany them.

The book is divided into four sections, representing the four stages in the journey – from Egypt to Sinai and on to the wilderness before finally coming home. While Egypt represents slavery, it also represents the status quo. This admittedly holds some appeal, given the dangers that await us in the wilderness. No wonder some never leave, unable to trust God or others in their quest for freedom.

Those of us who’ve been led out of Egypt, however, discover that the journey has only just begun. We find ourselves in Sinai – not the final destination by any means, but the place where we’re given our new identity as a free people who are called to live accordingly.

Charged with a whole new way of living we soon enter the wilderness where, as DeGroat puts it, “we’re faced with our worst fears and our greatest possibilities.” You don’t get through the wilderness in a day, and you don’t get through it unchanged.

On the other side of it all, after Egypt and Sinai and the wilderness, home awaits us: “a place where God smiles on us, dwells in us, and embraces us.” While our ultimate arrival is still to come, and though Egypt keeps pulling us back, we’re invited even now into the life of the kingdom.

There’s always the danger in a book like this of taking historical accounts and turning them into mere self-help material for people who in many ways enjoy a kind of freedom brick-makers in Egypt could hardly imagine. Fortunately, Chuck DeGroat mostly avoids these pitfalls by pointing throughout to the unchanging character of God in the face of all kinds of bondage. While as God’s people we continue to squander our freedom, turning again and again to lesser gods, the God who saved his people then stands ready to save his people still.

This review originally appeared at the Englewood Review of Books.