Looking Up

A wren of some sort (photo credit)

The first bird I added to my “life list” on the Merlin Bird ID app was a Canyon Wren. We were at one of our favorite places in Arizona, the Tonto Natural Bridge, with some of our very best friends, John and Judy. The day before, they had finally convinced Katie and me to download the app and join them as birders already.

Back behind the waterfall at the end of the trail, we craned our necks, trying to catch a glimpse of the birds up there, somewhere, on the walls of what is effectively a big natural tunnel. I waved my phone around like a crazy person, recording the birdsong. To my untrained ear it was quite the ruckus. The app describes their song, more eloquently, as “a gorgeous series of sweet, cascading whistles that echo off the rocky walls of its canyon habitat.” We never did spot them, but I’m told these camouflaged critters are “rich cinnamon-brown, with a salt-and-pepper pattern on the head and a neat white throat patch.”

Since then, with Merlin’s help I’ve identified such exotic species as the Great Blue Heron, the American Coot, the Yellow-rumped Warbler, and one of my new favs, the Western Tanager. On a lake in New Hampshire last month we spotted a Common Loon, which looks to be wearing a David Rose sweater and sounds like the spooky score to a horror film set deep in the rainforest.

A common loon (photo credit)

Closer to home, I’ve learned that the “boring blackbirds” in our yard are actually Great-tailed Grackles and the “dang pigeons” which defecate en masse on our shaded porch all summer are in fact Eurasian Collared-doves.

I’ve seen, heard, and learned all of this in—let’s see—a little under four months. Which is to say, I still don’t know diddly about birds. I haven’t yet purchased expensive binoculars or a Canon EOS R5 with a 100-500mm RF lens. I own exactly zero khaki vests. I’m an amateur.

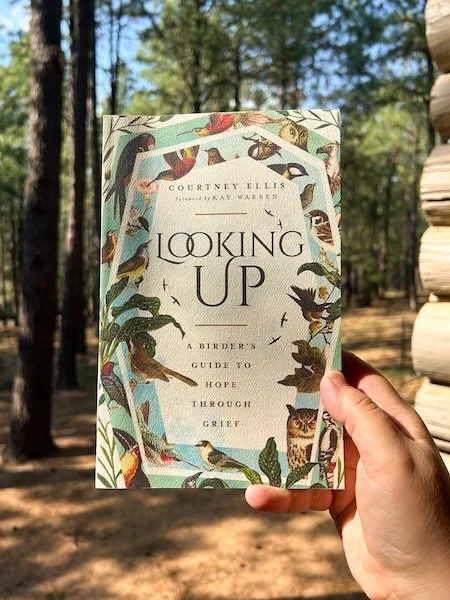

Which puts me in good company with Courtney Ellis, author of Looking Up: A Birder's Guide to Hope Through Grief(IVP). “I’m not a professional birder, or even an impressive amateur one,” she writes in the opening chapter. “My only qualifications for the birdy parts of this book are a deep fascination with all things avian and an even deeper love. Ilovebirds.”

It’s worth noting here that while “amateur” often has a negative connotation (as in “mere amateur”), the word originally comes from the Latin amator, which means “lover.” An amateur, then—in the truest sense of the term—is one who does something for the love of it. So why does Ellis love birding?

Because birds are amazing. Their biodiversity alone astonishes. There are hummingbirds that can perch on a strand of hair and pigeons the size of turkeys and cassowaries that could kill an adult man with a kick. Birds come in every color imaginable: black and white, pink and blue, iridescent greens and purples, translucent silver, spotted red. There are birds that can hear sound where we only recognize silence and birds whose songs are so complex they cannot be parsed by the human ear. There are birds that thrive in temperatures that would quickly freeze or practically cook a human. There are birds that clean up the dead. Some birds can mimic human voices; others sing hundreds of unique songs. Exquisitely beautiful birds give image to the Platonic ideal of perfection, while others look doodled by toddlers.

Looking Up has plenty of delightful passages like this about all kinds of avian wonders. But it’s also a deeply personal book, a memoir of losing a beloved grandfather. Ellis movingly recalls childhood visits to her grandparents’ home in northern Wisconsin, where her grandfather—“a man of few words and fewer pleasantries”—had put up bird feeders in the backyard. Here was a man who loved birds, who would tell his granddaughter about recent visits from orioles and robins. A real amateur, you might say. Ellis shrugged it off at the time. “I recognize now what he was saying to me in his bird reports. A kind of deeper, subtler way of speaking. A language unrecognizable until a person has suffered a great deal,” she writes. “He was telling me he loved me.”

Any day now, I’ve got a personal essay being published in Mockingbird. (What’s with all these birds all of a sudden?!) In it I make the case for paying attention to our own lives—including the painful parts—as a vital aspect of being human, as well as an essential way we love God and our neighbors.

So you know I smiled when I got to the passage in Looking Up where Ellis writes that birding is essentially about “paying attention, holding still, and opening up to the wonder of natural spaces. . . . It’s being present, right where we are, with what God has placed before us.” Similarly, she writes, “paying attention to grief” can be “an avenue toward hope.”

All too often, grieving people feel the pressure to hide their pain, to hurry up and be peppy again. Grieving people who are unable (or unwilling) to hide their sorrow can be made to feel like lepers, as more and more friends keep a wider and wider berth. The fear of contagion is a powerful thing. And so one of the things I appreciate most about what Ellis has done in Looking Up is the way she demystifies grief. “Every person is grieving,” she writes. “Every person in our pews. Every person on our highways, in our supermarkets, at our offices and schools. Each person on your street, in your home.”

Every person. If we’d only dare to notice.

To pay attention, then, is to love deeply. And loving deeply will hurt, whether beholding a rare endangered bird in the wild or holding the hand of a loved one in hospice. It was C.S. Lewis who wrote:

To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable.

For some people, I suppose, birding might be nothing more than a hobby, a small and meaningless luxury. People find ways to be joyless about gifts of all kinds. But when I consider Courtney Ellis, as well as my dear friends Judy and John, I see people well-practiced at paying attention. I see amateurs—people brave enough to love.