My Favorite Books of 2021

As is my custom, I’m delighted to give you my list of favorite books of the year just past.

First up, I so appreciate the nuance and grace that saturate the pages of Write Better: A Lifelong Editor on Craft, Art, and Spirituality (IVP, 2019) by Andrew T. Le Peau. This recent contribution to the genre of books about writing is, for me, right up there with Stephen King’s On Writing and Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird. Which, yeah, is saying something. Le Peau exudes what I’d have to describe as real bona fide encouragement — not what you’d necessarily expect from a lifelong wielder of red pens. I have to believe that the authors who have worked with Le Peau over the years have been blessed. For the rest of us, this generous distillation of the writing (and editing) craft might just be the next best thing.

I consider myself fortunate that writing constitutes a significant part of my job. It’s an alignment of work and calling that not everyone enjoys, and I don’t take that for granted. I believe that God cares about our Monday to Friday lives, what the Book of Common Prayer calls “the work you have given us to do.” And when it comes to bridging the gap between Sunday and Monday, the best book I’ve found is Work and Worship: Reconnecting Our Labor and Liturgy (Baker Academic, 2020) by Matthew Kaemingk and Cory B. Willson. I wrote about it here.

Speaking of the pursuit of more integrated lives, this year I read Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma (Penguin, 2015) and I’m really glad I did. A psychiatrist and researcher who clearly loves his work, Dr. van der Kolk unpacks what the latest research reveals about how our bodies hold onto trauma — and ultimately how we can heal. As a survivor of a home invasion by masked gunmen when I was ten, this book (along with therapy) has helped me begin to understand some of the more subtle ways trauma has remained trapped inside of me, even while I’ve managed to live what would appear to be a mostly normal life. “We have learned that trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is also the imprint left by that experience on mind, brain, and body,” van der Kolk writes. “This imprint has ongoing consequences for how the human organism manages to survive in the present.” Fortunately, however, “As human beings we belong to an extremely resilient species.” Thanks be to God for that.

Marilynne Robinson’s Jack (Picador, 2020), the latest novel in her Gilead series, is about an agnostic son of a preacher, a rambler who second-guesses and self-sabotages himself, over and over and over again. He makes bad moves and bad jokes. He takes in a stray cat. He takes a beating or two or three (not from the cat). He believes in divine election and suspects he falls on the wrong side of the equation. And still we root for him. I have a bit more to say about this marvelous, meditative story here.

Another novel I want to mention here is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah (Knopf, 2013). It’s a book about complicated connections — between people and places and identities. It’s about the mysterious threads at the heart of those of us who live between cultures. Get this, when the main character has returned to Nigeria after a long time in the United States: “He had not merely said ‘welcome’ but ‘welcome back,’ as though he somehow knew that she was truly back. She thanked him, and in the gray of the evening darkness, the air burdened with smells, she ached with an almost unbearable emotion that she could not name. It was nostalgic and melancholy, a beautiful sadness for the things she had missed and the things she would never know.”

Carolyn Forché’s memoir What You Have Heard Is True (Penguin, 2019) reads like a thriller. As a twenty-something poet living in California in the late 1970s, Forché is surprised and puzzled when a Salvadoran man named Leonel shows up at her house, invites himself in, and without explaining why, launches into a days-long lecture on El Salvador’s history, culture, and politics, scribbling elaborate diagrams on her dining room table using butcher paper. For reasons that defy logic, Forché doesn’t kick him out, even when he keeps ignoring her queries about why he’s there and what he wants. Even when she hears a rumor he may be with the CIA. Or he may be a Marxist guerrilla. Or a mercenary. Or a humanitarian. No one really knows. She certainly doesn’t. Eventually, Forché follows him to El Salvador, a country on the brink of civil war, and things get really dicey from there. In the spirit of the mysterious Leonel, let me just say this: the less you know about this book before you read it, the better.

David Swartz is one of those rare scholars whose work I’m always eager to read. I included his first book in my 2012 favorites list. And now, I’m adding his latest, Facing West: American Evangelicals in an Age of World Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2020). Here, Swartz (re)narrates the ways in which North American evangelicals have been – and continue to be – shaped by believers from the Global South, often in unpredictable ways. He also reveals that the historical narratives we’ve inherited sometimes tell only half the story. I have more to say about this important and illuminating book here.

As we approach the end of this year’s favorites, let’s throw in a twofer. I read two books of essays by Teju Cole. First was Known and Strange Things (Random House, 2016), followed by the brand new Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time (University of Chicago Press, 2021). Cole’s prose is jaw-dropping at times, and in just about every essay, his curiosity and imagination are on full display. I’m never quite sure where he’s going, but I’m always glad I’m along for the ride — even when the journey leads to dark places. Earlier in the year, I wrote a few words about the theme of “in-betweenness” that I find so compelling in Cole’s writing.

What can I say? Tish Harrison Warren has done it again. Drawing from and building upon one of the most beautiful and devastating prayers you’re ever likely to encounter, Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep (IVP, 2021) is simply stunning. I read this one early in 2021, and my goodness, I needed it. We all do, I’d say. Harrison shares personal and pastoral reflections as she moves phrase by phrase through the beloved Compline prayer that Christians have been praying – through plague and famine, war and peace, thick and thin – for centuries. I wrote a bit more here.

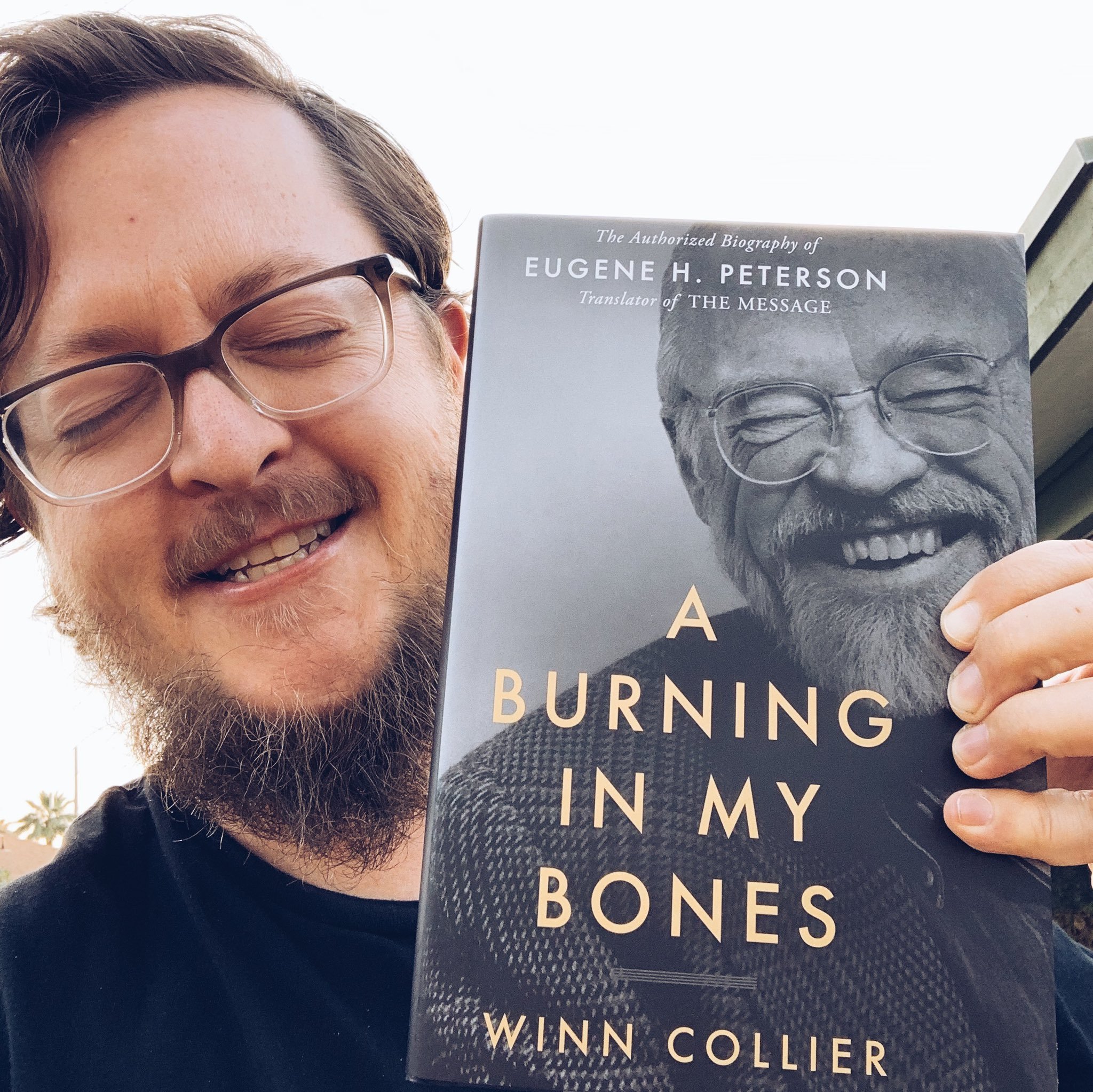

Back in 2011, prompted by some interesting discoveries in Eugene H. Peterson’s memoir, I wrote about the Hoilands of Stavanger, Norway – Eugene’s ancestors and mine. Ten years later, it has been fun seeing those same Hoilands make some noteworthy appearances in A Burning in My Bones (Waterbrook, 2021) the authorized biography of Peterson by Winn Collier. But that’s not why I read this book, and it’s not why you should either. You should read it because it’s the story of an astonishingly ordinary life, marvelously told. Collier writes not just as a biographer, but as a trusted friend. This isn’t hagiography, nor is it exposé. Instead, it’s an intimate exploration of the people, places, and events that made Peterson into the person he became. Needless to say, the man who would eventually write A Long Obedience in the Same Direction took some strange detours to get there. I’m so glad we have this book. And I’m glad Winn Collier is the one to write it for us. It’s my favorite book of the year.