Six Lessons from MLK

Earlier this year, around the time I saw the unforgettable film Selma and while many of us were doing some soul-searching following the tragic deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, I read the autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.

In the weeks since I put it down, I’ve continued to reflect on King’s remarkable life. So I thought I’d share six lessons that have stayed with me.

1. Faith. First of all, I was reminded of the central role that religious faith – and Christian faith in particular – played in the civil rights movement. This is a point that was driven home to me a few years ago in Welcoming Justice, a wonderful little book by John Perkins and Charles Marsh, the latter of whom argues: “Only as long as the Civil Rights movement remained anchored in the church — in the energies, convictions and images of the biblical narrative and the worshiping community — did the movement have a vision.” Thanks to King’s leadership, the movement maintained that foundation for many years.

2. Restraint. During Selma I marveled at the remarkable self-discipline that was evident among so many of the civil rights movement’s leaders and participants. Think of the restraint of Annie Lee Cooper (played by Oprah Winfrey) in the scene when she tries, once again, to register to vote. She does everything the law requires of her and then some, but the registrar – who personifies a racist, unjust system – continues to intimidate her and thwart her efforts. He can deny her the right to vote, but he is unable to take away her dignity. At several points in King’s autobiography, I was struck by the transformative power of “turning the other cheek” – something that so many contemporary movements in the name of “rights” completely miss.

3. Specificity. One of the underlying aims of the civil rights movement – if not the aim – was to say and demonstrate that, in King’s words, “all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics” are made in the image of God. As such, every man, woman, and child is a person of equal value in the eyes of God. But in order to reach this aim, King knew the movement had to get down to specifics, so they marched and went to jail and were killed while emphasizing specific things that served to dehumanize and oppress – hence targeted campaigns involving buses and lunch counters and so on. Vague generalities about human dignity wouldn’t get local officials to budge. But campaigns with tangible economic ramifications – coupled with vivid images in newspapers and TV screens – did. And what started small and city-specific soon changed the national landscape. “Cities that had been citadels of the status quo,” King wrote, “became the unwilling birthplace of a significant national legislation. Montgomery led to the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960; Birmingham inspired the Civil Rights Act of 1964; and Selma produced the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”

4. Rhythms. When considering everything the civil rights movement accomplished during a relatively small window of time, you might assume that King and other leaders worked nonstop. In his autobiography, he doesn’t go into a lot of detail about what he did to relax and recharge, though there is no doubt that prayer was instrumental. But when you consider the timeline of his adult life, you notice that there were months, and even years, between major campaigns. Even if these periods of time weren’t spent vacationing in the south of France, it seems he understood the need to periodically retreat from the limelight.

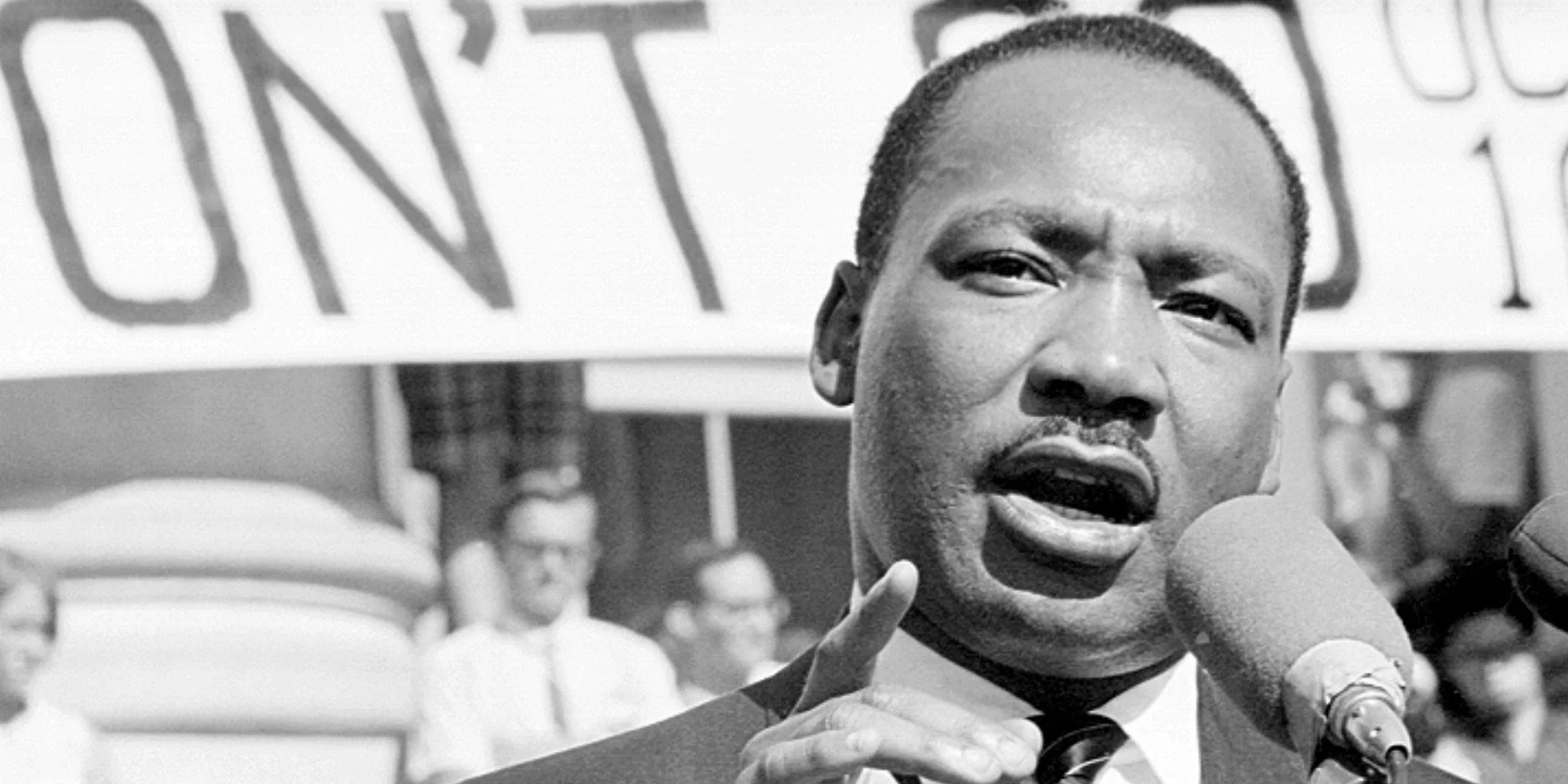

5. Leadership. During marches, King was at the front. This was good for photo ops, to be sure, but it also meant he was the first to receive blows from police billy clubs. He was the first to go to jail and in many cases the last to leave. True, it does seem there were some issues and conflicts between him and other leaders of the movement, and those are as essential to King’s story as his virtues. But at his best – at the movement’s best – King led by example, not from a cozy command center in some secure location. A leader is not greater than the movement.

6. Personhood. King understood that victims and perpetrators of racial injustice were both enslaved, and therefore both were in need of being set free. He put this eloquently in his speech in Montgomery, which is portrayed near the end of Selma: “Our aim must never be to defeat or humiliate the white man but to win his friendship and understanding. We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. That will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.”