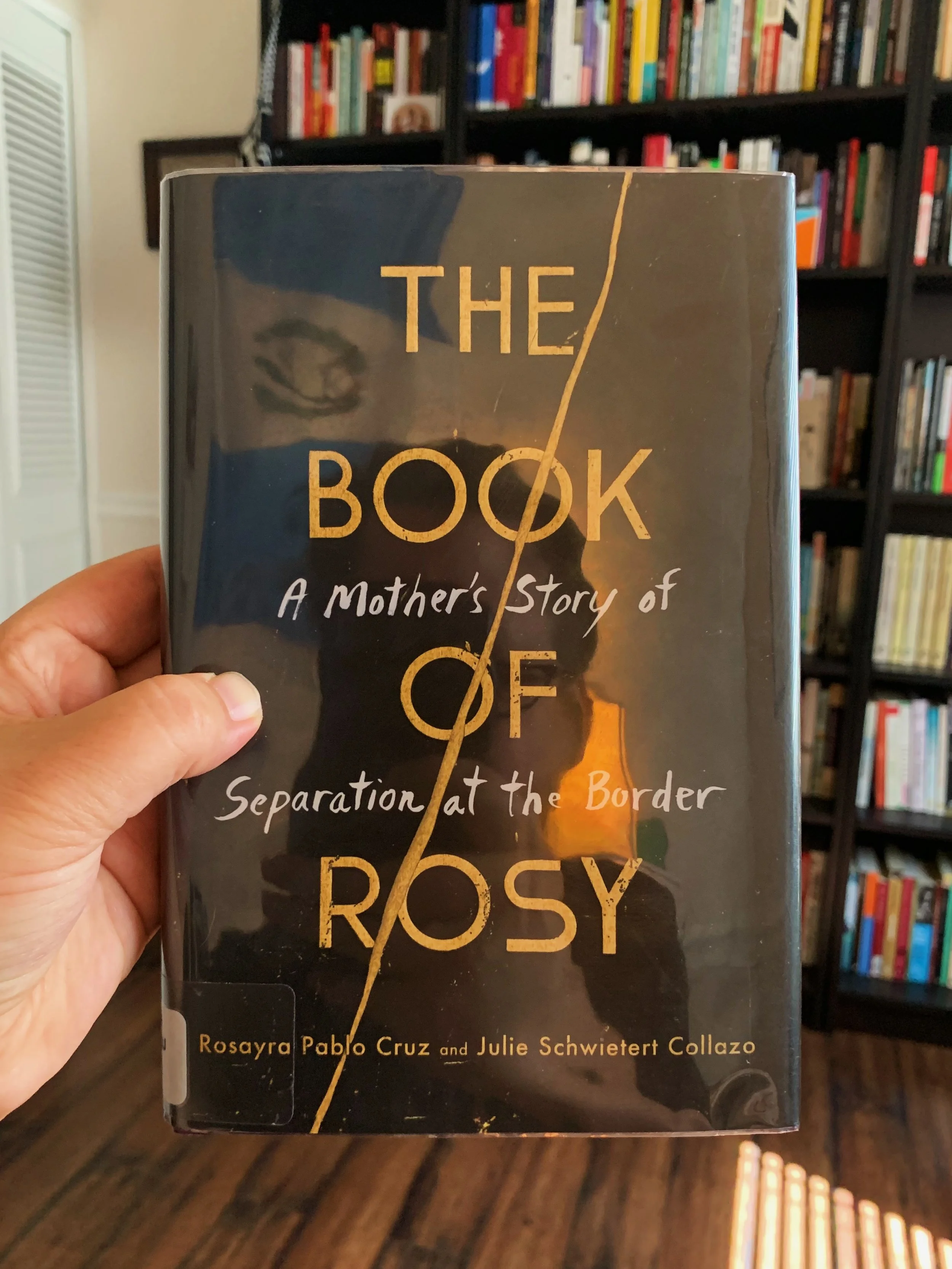

The Book of Rosy

“Among the many things that people don’t understand about migration is this: No one wants to leave the people they love. Most people don’t want to leave the land where they were born, or the soil where their umbilical cord was buried. If they believed that staying would ensure survival, they would never set off on such a treacherous journey.”

That’s Rosayra Pablo Cruz in The Book of Rosy: A Mother's Story of Separation at the Border (HarperOne), coauthored by Julie Schwietert Collazo, and it’s something I’ve heard in conversations time and again. I heard versions of this when I worked with Cuban refugees in Pennsylvania. I’ve heard it here in Phoenix among asylum seekers from places like Colombia and Venezuela. And I hear it from people in the communities where 1MISSION works in Mexico: “No one wants to leave the people they love.” That is, unless they feel they no longer have a choice.

It’s difficult for many of us to grasp the impossible choices that vulnerable families are forced to make to survive. This is why I’m especially grateful for books like this one, cowritten by a Guatemalan woman who sought—and was granted—asylum in the United States.

After making the arduous journey north through Mexico and into the United States, Rosy is separated from her sons at a prison in Eloy, Arizona. They are apart not for a matter of hours or days, but for months. Meanwhile, Rosy is left in limbo, in every sense of the term. “The isolation, the desolation…” she writes, “this is why the prayer circles [among detainees] are sustenance, a ray of light and a breath of hope in an otherwise dark and airless existence inside Eloy. If my own prayers are not sufficient—and I’d begun having some doubts that they were effective—I feel certain the collective invocations of so many mothers could reach God’s ears and touch His heart.”

This particular story has a happy ending. But not all stories like Rosy’s do. While the ability to seek asylum is a right guaranteed by law, nearly two-thirds of asylum seekers in the United States eventually have their cases denied.

As Rosy and her sons are reunited in New York (that’s where the sons had been sent by the powers that be), we find them being cared for by a Jewish community of people who understand, in their bones, what it means to be a stranger in a strange land. Rosy is not yet legally allowed to work, but her sons enroll in school, and Rosy surprises everyone—including herself—by running for and being named co-president of the school’s PTA.

“We are grateful for any support,” Rosy writes of the family’s experience in their new home, “but we’re not waiting for a handout. We want to be part of your American dream. We want to help you realize it. We want to share in it with you.”