The Joys of Anticipation

Anticipation.

It’s one of my favorite things in the world. And of all the things in the world to anticipate, travel is one of the best. In the days, weeks, and months leading up to a trip, I begin to anticipate and imagine all we might taste, touch, see, smell, and hear. What’s more, I anticipate how it might feel to be tasting, touching, seeing, smelling, and hearing those things. Whatever I anticipate, plenty of surprises await—and these, too, are gifts.

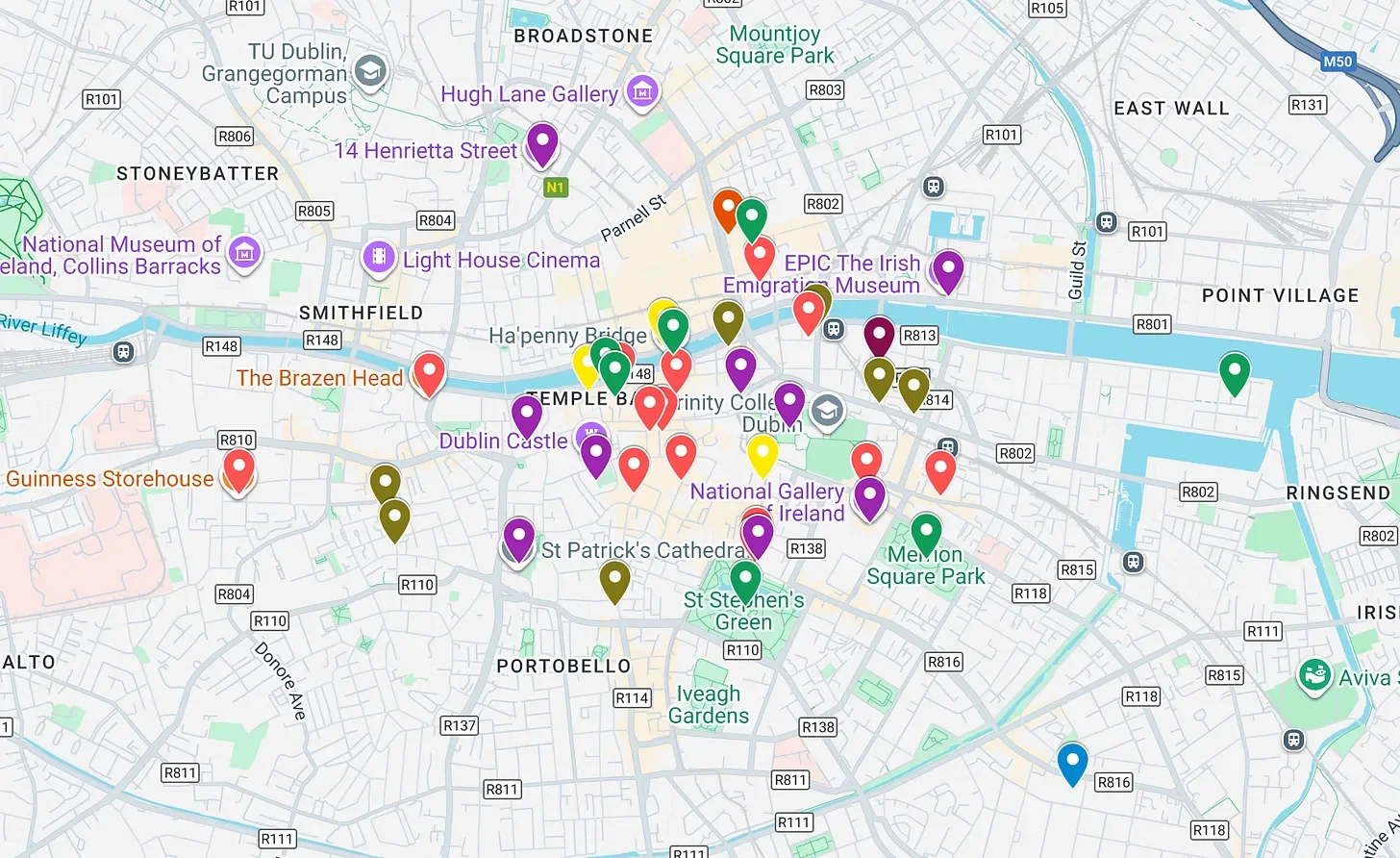

Being a certain kind of nerd, part of the joy of anticipating travel, for me, is creating a Google Map with color-coded pins. Red pins for restaurants and watering holes. Brown pins for coffeeshops. Purple pins for museums and churches. Green pins for, well, green spaces. And yes, you better believe it: yellow pins for independent bookstores.

A map of possibilities in Dublin.

For the better part of a year, I’ve been gratefully and eagerly anticipating what in so many ways promises to be a dream trip to the British Isles. With a wonderful group of fellow writers from my seminary program, this month Katie and I will go on a literary tour, visiting significant spots in the lives (and deaths) of such luminaries as Austen and Joyce, Wordsworth and the Inklings. (It’s a tremendous privilege to be able to go on a trip like this, and I don’t take it for granted. Which also means I’m committed to making the most of it.)

Our group’s itinerary is already ambitious—Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales, and England in a little under two weeks—but that hasn’t stopped me from daydreaming about possible side visits to bookstores. In Dublin, I dropped a pin for Hodges Figgis, Ireland’s oldest bookshop; having opened in 1768, it’s twenty-nine years the senior of Hatchards, the oldest in the UK. In the North, I marked Keats & Chapman, whose no-frills website sadly claims the distinction of being “the last independent bookstore in Belfast city centre.” Over in London, Foyles in Soho brags about “four miles (6.5km) of book shelves . . . on six floors,” while the “Edwardian bookshop” Daunt Books in Marylebone boasts “long oak galleries and soaring windows.”

So many pins, so little time.

+ + +

But pins on maps will only get you so far, literarily speaking. So for the past year I’ve also been reading books by and about authors from the places we’ll go. Some of them have been assigned for my program, but many more have been, let’s just say, “off list.”

Anticipating our visit to the Book of Kells in Dublin I read How the Irish Saved Civilization by Thomas Cahill. To better grasp the ways Ireland has changed in recent decades, I read Fintan O’Toole’s We Don’t Know Ourselves. For another taste of Faha—my favorite fictional Irish town by a country mile—I read the latest novel from Niall Williams, Time of the Child.

In preparation for a brief stop in Oxford, I’ve brushed up on Tolkien, Lewis, and the Inklings. Because this year marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of Jane Austen—and because the tour takes us to Bath—I picked up Persuasion, having read Pride & Prejudice a few years ago. And earlier this year, somberly (and, at times, angrily) I made my way through Marilynne Robinson’s apparently forgotten 1989 work of grim nonfiction, Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution.

+ + +

Following my curiosities, I also found myself taking an unexpectedly deep dive into the lives and works of three poets whose stomping grounds we’ll either visit or pass through: Seamus Heaney, Gerard Manley Hopkins, and R.S. Thomas.

I’d like to say a a few words about each.

Seamus Heaney

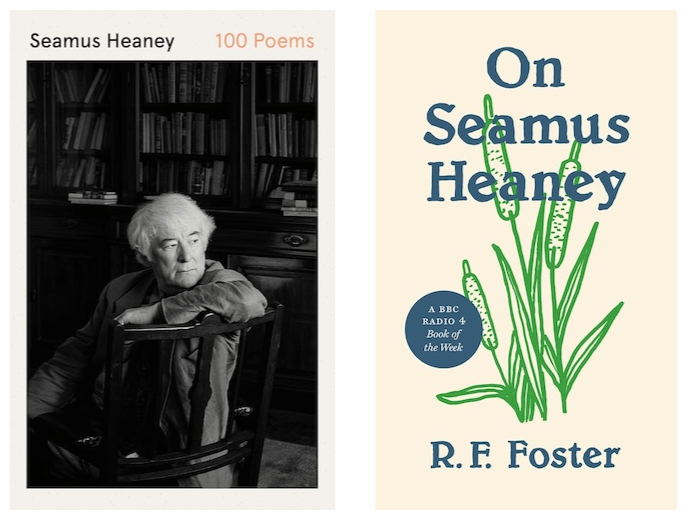

100 Poems was assigned, and my goodness is it a treasure trove. I’d like to memorize about fifty of them, though I should probably start by memorizing one.

From the seminary library I borrowed The Place of Writing and copied down this quote, in reference (if I recall) to a poem by Heaney’s countryman Louis MacNeice: “This poem does not purport to tell us how to act in the poll-booths in Northern Ireland. It is not a great rallying call such as sects and cults are founded upon, but it is nonetheless a clarification, a momentary stay against confusion.” Poems can offer us that kind of thing.

Right now I’m reading On Seamus Heaney, a short, accessible introduction by R.F. Foster, written “in the light of the poet’s life and the historical circumstances surrounding it”—including, of course, the Troubles which convulsed Northern Ireland in violence for so many years.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Before really immersing myself in Hopkins’ poetry—it’s not the easiest thing in the world to read—I enjoyed Catharine Randall’s excellent A Heart Lost in Wonder, “an interpretive biography, a life viewed through the prism of theology.”

On our trip we’ll visit St. Beuno’s Jesuit Spirituality Centre in North Wales, where Hopkins received his theological training. It’s also where he composed The Wreck of the Deutschland, one of his major poems. So I was intrigued by (but ultimately mixed on) Ron Hansen’s Exiles, a work of historical fiction interweaving the stories of the five German nuns who died in the shipwreck with the story of Hopkins writing the poem.

Finally, I returned to the poems themselves. This time around, I picked up As Kingfishers Catch Fire, a recent collection edited and annotated by Holly Ordway. In her introductory remarks Ordway writes:

It is not possible to do a quick read and “get it.” He does not permit us to have a consumeristic, utilitarian approach to poetry (or to prayer). We must slow down; we must try, as much as possible, to give ourselves time to reflect, to make connections, to meditate on the images and phrases of the poem, to see how they challenge us—how they make us stretch, as Hopkins stretches the syntax of the poem and the limits of language.

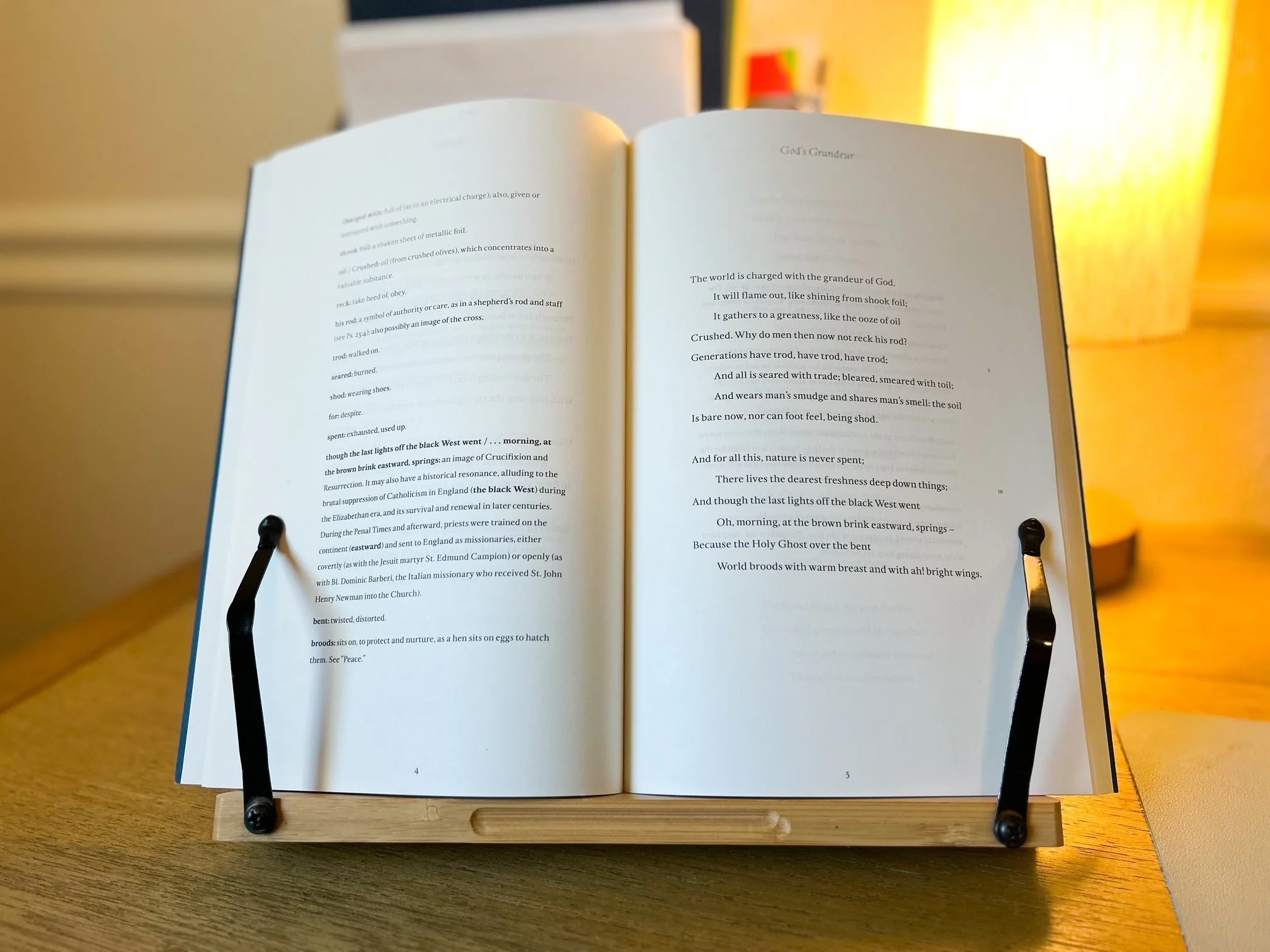

The book is laid out in such a way that when it is opened in front of you, Hopkins’ poetry appears on the right-hand page with Ordway’s annotations on the left. Ordway’s encouragement is to first read the poem in its entirety (aloud, if possible), then to read the annotations, before reading through the poem again. Doing this, I found myself entering more fully into the scenes Hopkins wants us to experience. I’ve always found the language in these poems beautiful; now I’m beginning to grasp some of the layers of meaning.

“As Kingfishers Catch Fire” by Hopkins, with annotations by Holly Ordway.

R.S. Thomas

I’m going completely off list here, but here’s why: almost a year ago, when I told a few people about an essay I was then in the process of writing, not one but two friends sent me his poem “The Bright Field.” (Look it up; it’s beautiful.) Right away I knew I needed to familiarize myself with the work of this Welsh poet and Anglican priest who served in out-of-the-way places—a “vicar of large things in a small parish,” who absolutely paid attention to his life.

To get my bearings, I first reached for Strangely Orthodox: The Religious Poetry of R. S. Thomas, an itty bitty (and odd) book by Barry Morgan, the former Archbishop of Wales. “His daily pattern,” Morgan writes, “was to spend the morning studying, go for walks in the afternoon and in the evening visit his parishioners since it was no use visiting them in the day when they would be out on the farms working.”

Then, in one sitting last weekend I read The Echoes Return Slow, published when Thomas was 76. Half poetry, half third-person prose, in this memoirish collection he looks back on his life, his vocation, his family, his places. Welsh weather looms large. Here he is adjusting to retirement:

From a parsonage to a cottage. The poverty of the spirit must be extended to the flesh, too; books given away, furniture dispensed with; paintings that give colour to expanses of white wall, stored away in the loft. A four-hundred-year-old cottage, that remembered centuries of Welsh tenancies. Nothing between them, too, but the unrendered slates. It was a sounding-box in which the sea’s moods made themselves felt.

One of my favorite books of the year. Easily.

+ + +

My hope in reading all these books—and specifically, these three poets—is that when we arrive in Dublin, and as we meander through cities and hilltops and valleys en route to London, I’ll be able to remain more fully present to the experiences that await me, await us.

When we visit Giant’s Causeway, I’ll think of Heaney, who calls it a “basalt throne,” and will wonder what that means. With Hopkins, I’ll keep my eyes peeled for anything shining like “shook foil.” And on the Jane Austen portion of the tour, you better believe I’ll find a way to sneak this fabulous Northanger Abbey line into conversation: “Would you have us laughed out of Bath?” (Pray for me in navigating the pronunciation; in theory, two of those words should almost rhyme.)

In Wales, when we hoof it up the hill through fall foliage to Sunday worship at the village church of Llantysilio, perhaps with Thomas I’ll wonder: “How far can one trust autumn thoughts? Against the deciduousness of man there stand art, music, poetry. The Church was the great patron of such. Why should a country church not hear something of the overtones of a cathedral?”

Reading all these books is part of the joy of anticipation. These poets and priests, journalists and novelists and theologians, they’re all inviting me to show up, be present, pay attention. And then, quite possibly, to be dazzled.

“Known and strange things” await us, as Heaney says, coming at us sideways, prone to “catch the heart off guard and blow it open.” Amen, may it be so. Not only on literary tours, but every day, everywhere.