The News

About halfway through college, at the recommendation of my academic advisor, I decided to pick up a minor in journalism. Only it wasn’t called that anymore. For some odd reason, TPTB had decided to bestow upon this minor a newfangled (but somehow already antiquated) name: Print Media Studies.

I enjoyed my journalism classes very much and went on to do some writing that appeared in magazines. But the ensuing decade was a distressing one for anyone invested in the future of print anything. Between daily newspapers going out of business and massive bookstore chains shuttering their doors, the third millennium AD was off to a rocky start. It was beginning to seem as though I’d accidentally earned a minor in history.

But lo and behold, it’s 2017 and print still has a pulse. While the number of daily newspapers dropped nearly 10% over a ten-year period, as of 2014 there were still 1,331 of them in the United States – an average of more than 26 per state. And the market for print books, while still shaky, is actually growing – something the prognosticators of ten years ago would not have anticipated.

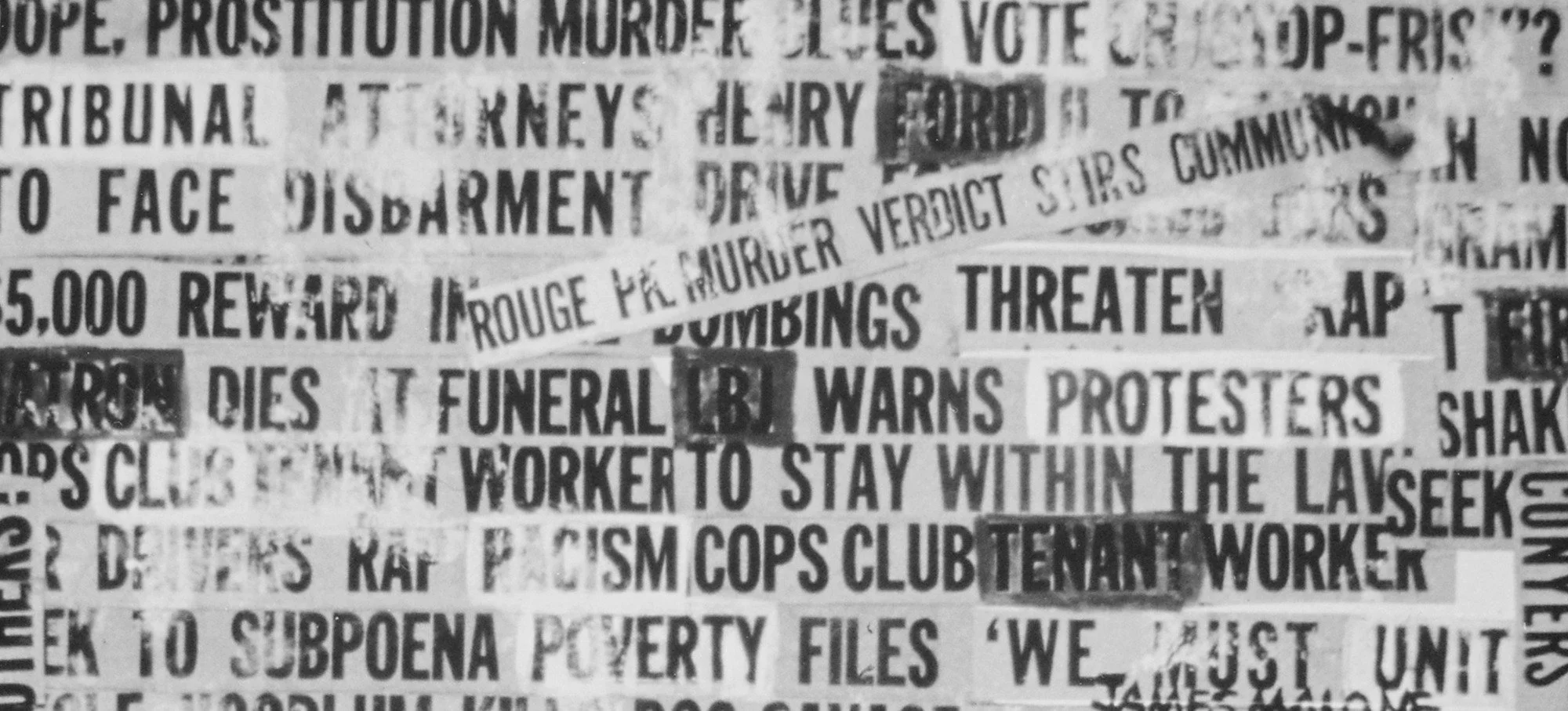

All the same, the news organizations we broadly refer to as “the media” face challenges that run far deeper than the economic disruptions of the digital revolution. They face nothing less than a crisis of believability, particularly when it comes to politics.

That’s why this is as poignant a time as any to pause and ask some big questions about the news: What public service should news organizations exist to provide? How do we decide which news outlets deserve our attention and patronage? What are the news-related dangers we should be careful to name, and if possible, avoid?

When it comes to asking incisive questions about aspects of society we are prone to take for granted, the philosopher Alain de Botton is our guy. His books have asked “why” questions about subjects as diverse as travel, work, and architecture. Those philosophical questions now continue in The News: A User’s Manual.

With thematic sections focused on politics, world news, economics, celebrity, disaster, and consumption, de Botton assesses the tendencies of news organizations related to each category of coverage and suggests what “the ideal news organization of the future” might do to better fulfill its unique obligation to society.

The news, de Botton argues, has a responsibility not only to remind us of everything that’s going wrong but also “to train and direct [our] capacities for pride, resilience and hope.” While a nation can enter into decline due to “sentimental optimism,” it’s also possible for such a decline to be precipitated by a kind of “media-induced clinical depression.” He continues:

Alongside its usual focus on catastrophe and evil, the news should perform the critical function of sometimes distilling and concentrating a little of the hope a nation requires to chart a course through its difficulties. While helping society by uncovering its misdeeds and being honest about its pains, the news should not neglect the equally important task of constructing an imaginary community that seems sufficiently good, forgiving and sane that one might want to contribute to it.

I agree it would be agreeable if the news media were to perform this “critical function” with consistency. But I also recognize that most of the time we get the news coverage we deserve. It’s hard enough for news organizations to make a viable go of it anyway; why undertake the risk of investing in virtue-inspiring “celebratory journalism” when all that most of us actually want is a daily dose of envy and excitement, anger and fear?

Fortunately, alternatives do exist – as do citizens who support them. As for me, one of the qualities in journalism I especially value is breathing room. I find this quality in some of the online pieces that have come to be known, weirdly, as “longreads.” It can be found in lengthy, well-researched works of reportage in magazines, like this and this. And there is plenty of it in documentaries, podcasts, public radio, and, of course, in full-length books by journalists. I don’t expect any of these platforms or outlets to vanish anytime soon; and if I’m right, all it means is that there are many others who, like me, continue to value the existence of reporting and nonfiction storytelling that has been given room to breathe – even if it requires more of our time, even if (gasp!) we need to pay for it.

This idea of journalistic breathing room is especially critical when it comes to news of events that take place outside the normal parameters of our daily lives – precisely because we know so much less about the people who live, work, and play where we don’t.

“Unless we have some sense of what passes for normality in a given location, we may find it very hard to calibrate or care about abnormal conditions,” de Botton writes. “We can be properly concerned about the sad and violent interruptions only if we know enough about the underlying steady state of a place, about the daily life, routines and modest hopes of its population.”

Yet this kind of context is all too often entirely absent, especially (but not exclusively) in world news. The problem, de Botton says, is that “we don’t know whether anyone has ever had a normal day in the Democratic Republic of Congo” or “what it’s like to go to school or to visit the hairdresser in Bolivia” or “whether anything like a good marriage is possible in Somalia” or “what people do on the weekend in Algeria.”

Because we only hear about disasters and unrest in these places (when we hear about them at all), we can’t identify with the everyday lives of ordinary people there, which means we struggle to care about them when they fall victim to calamity.

Seen in this way, journalism with breathing room shouldn’t be viewed as a distraction from “hard news” but rather “the bedrock upon which all sincere interest in appalling and disruptive events must rest.” Which leads de Botton to this proposal:

The ideal news organization of the future, recognizing that an interest in the anomalous depends on a prior knowledge of the normal, would routinely commission stories on certain identification-inducing aspects of human nature which invariably exist even in the most far-flung and ravaged corners of our globe. Having learned something about street parties in Addis Ababa, love in Peru and in-laws in Mongolia, audiences would be prepared to care just a little more about the next devastating typhoon or violent coup.

Ideally, the thinking goes, a citizen who makes a habit of staying informed about local, national, and international news would be less ignorant, less prejudiced, and more intelligent. But de Botton knows it doesn’t always work out that way. “In its scale and ubiquity,” he writes, “the contemporary news machine can crush our capacity for independent thought” – which is just to say that as with everything else in life, we should handle the news with care.

My encouragement, for what it’s worth, is twofold: First, avoid at all costs the purveyors of news whose business model is built on propagating fear and rage. Seek factual, verifiable reporting from multiple sources as well as commentary that can be characterized as calm and principled (which doesn’t have to mean “boring”). You may have to dig a bit to find these folks; they’re out there, but are often drowned out by louder, brasher voices. Then, once you’ve identified these journalists, commentators, and outlets, support them.

The idea that a free, independent press is essential for the flourishing of society is not a new one, nor should it be controversial to say as much. If by chance you encounter reporters on the street, in the workplace, or (much more likely) on social media, do something revolutionary: thank them for their public service.