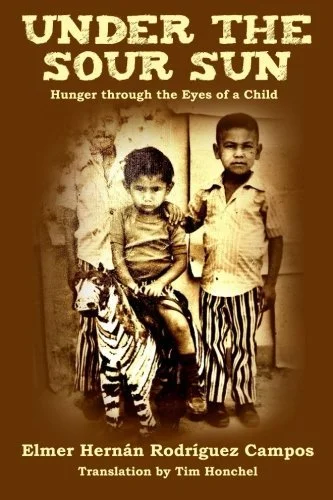

Under the Sour Sun

I’m sure you know the line: “They have so little, but they’re so happy!” How many times have you heard a variation of that? How many times have you said it yourself?

The truth is, for those of us who live on more than $2 a day – that is, for everyone who reads the Englewood Review of Books – it is decidedly difficult to talk about poverty without the conversation quickly devolving into cliché.

That’s why I was particularly intrigued by Under the Sour Sun, a firsthand account by Elmer Hernán Rodríguez Campos, a Salvadoran man who grew up in La Costra (“The Scab”), the municipal dump on the outskirts of San Salvador. “This is not the story of a person that began poor and ended up immensely rich,” he writes. Rather, it is “a peek through a crack of a life like many others: a childhood shared by thousands of children born in Central America, plundered and bankrupt.”

Rodríguez Campos describes learning to sift through the trash at a young age, searching for items that could be fixed and resold. “Those who grow up rich have always had the habit of throwing away things that still have some use, above all electric appliances,” he writes. “These things are thrown out at the first small sign of defect and fall into the hands of the poor, who with a little patience and intelligence, repair them and return them to life.” Every time he would chance upon one such treasures, he recalls, “I would plead fervently with God that he would never, never take away this good habit from the rich.”

As a child, Rodríguez Campos was not self-consciously poor – “poverty arrived only when an adult mentioned it” – but he was intimately acquainted with hunger. “Hunger is real and I know it because I spent my entire childhood hungry,” he writes. “I went to school, played, and slept, always hungry.” As an adolescent he also became conscious of the painful realities of social and political exclusion, writing, “We carried within us the sad reality that to the government and outside world, we did not exist.”

As the story moves from the 1970s into the 80s, Rodríguez Campos gives us a glimpse into life in El Salvador as the country descended into civil war. At a certain point we meet his uncle David, an uncanny Che Guevara figure (right down to the asthma) who provided medical services to the community free of charge, but could never stay in one place very long on account of his revolutionary views. This uncle’s story reveals on a micro scale that in El Salvador’s conflict, like those in neighboring countries at the time, battle lines were drawn not only between military governments and armed rebels, but between neighbors and even family members, leading to generational wounds that persist to this day.

As fighting intensified, the problems for those living in The Scab compounded. Bodies began appearing in the streets. So too, however, did the relief supplies – wheat, vegetable oil, and powdered milk, delivered by military vehicles. It was understood that the U.S. was behind these provisions. “The gringos send us all of this so that we don’t die from hunger,” the author’s mother would explain. A short time later, however, helicopters began appearing overhead. “The military troops’ boots were sticking out both sides of the helicopters and on the underside, on the belly of those devices, were the large letters: USA.”

Eventually, Rodríguez Campos and his family managed to escape, and he and his mother were granted refugee status in Costa Rica, where he now lives and works as a painter.

In a certain sense, this is not an extraordinary book. Those familiar with the broad contours of recent Central American history will find few surprises here. But the real value of Under the Sour Sun is found in the nuances that are there simply because this is a story that has been lived – not just researched and analyzed. Sit with these nuances long enough and you’ll find that the familiar clichés begin to lose their viability. True, the childhood of Rodríguez Campos had its fair share of joy and sorrow alike. But his story is far more complex than a simplistic juxtaposition of happiness and deprivation, and for that reason it warrants the attention of those who would understand what it is to be poor.

This review originally appeared in the Englewood Review of Books.