Wannabe Revolutionaries

Over the course of a few visits to Changing Hands (a fantastic independent bookstore in the Phoenix area), I’ve picked up a handful of books. As it happens, two of them happen to be first-person stories of people who moved to Latin America and joined rebel movements. Or tried to.

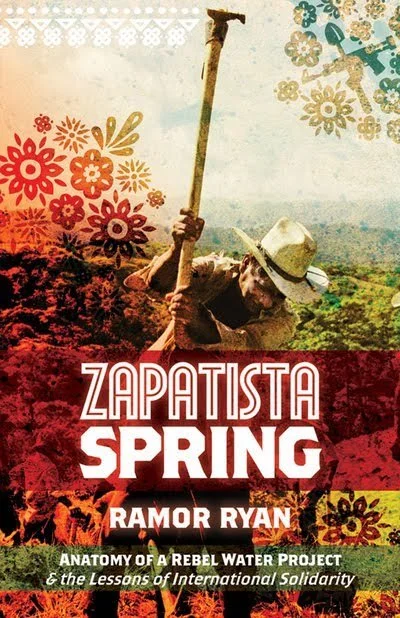

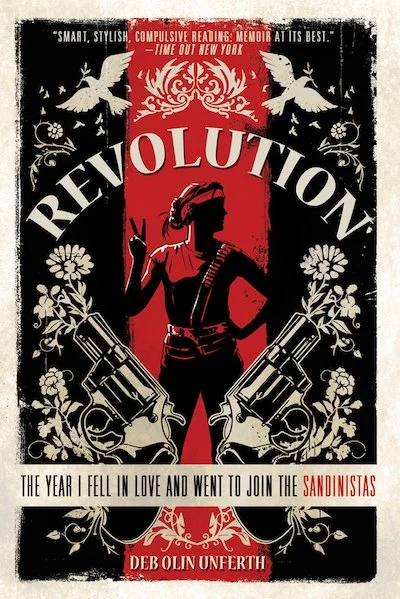

The first is Zapatista Spring: Anatomy of a Rebel Water Project & The Lessons of International Solidarity (AK Press) by an Irish writer named Ramor Ryan, set in Chiapas, southern Mexico. The second is Revolution: The Year I Fell in Love and Went to Join the Sandinistas (St. Martin’s Griffin) by Deb Olin Unferth, which takes place primarily in Nicaragua, with experiences elsewhere in Central America as well.

Both set out for their destinations in Latin America with youthful idealism and romanticized views of poverty and of the revolutions in their respective countries. Both come away disillusioned. While I doubt that many readers of this blog are contemplating joining armed rebel movements, I think there are lessons for all of us in these two true tales.

In Zapatista Spring, Ramor Ryan and his friends go to Chiapas “in solidarity” with the Zapatistas, to support the revolution by helping them with a water project that will enable them to survive more or less off the grid. But their sense of solidarity is dashed and their ideals are thrown into question when they discover the peasants are actually fairly conservative, very patriarchal, persistently religious, and for the most part uninformed about the revolution. While the outsiders romanticize life among the poor in Chiapas, thinking of the purity of their cause, the people there want to know how much plane tickets cost, how much revolutionary chic clothing costs, and whether they could find work in the US or Europe where the outsiders are from. And while the gravitas of Subcommandante Marcos’s poetic wit in his written communiques is what drew people to Chiapas from all over the world, the people in this town haven’t read them; those things are irrelevant to their daily lives.

The outsiders’ idealism and the pragmatism of the poor clash at every turn. Ryan and his friends later learn that the people in the village had gone on to defect from the Zapatistas, accepting the government party’s offer of support. It had been, after all, about pragmatism all along; the outsiders turned out to be the fools.

Unferth’s Revolution might lack some of the serious depth of Zapatista Spring, but in the end her experience is very much the same. She sets out with her college boyfriend to join the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, only to find that they are unwanted.

In effect, they get fired from the revolution. So they bounce around revolutionary Central America on what turns out to be a long and pointless (but for us, very funny) journey. Finally, after leading the reader through a seemingly endless series of wince-inducing illnesses and other bizarre predicaments, Unferth’s sole desire upon arriving again on American soil is, of course, McDonald’s.

Many of the people I know who have spent time among the poor in Latin America have done so as part of church mission trips, not as part of rebel armies. But the lessons from the stories in these books raise important questions for all of us.

Here are some questions that come to mind…

1. Why do we want to be among the poor in the first place? Is it because of a romanticized view of the poor or their poverty? Is it out of a sense of pity? A sense of duty to our cause? Do we do it with a sense of “solidarity”? Do we do it because we want an adventure? Do we go so we’ll have good stories to tell our friends? Do we know why we want to do it?

2. Are we welcome among the poor? Whose idea was it for us to be there? Were we invited? Did we invite ourselves?

3. When we arrive, what’s our posture? Do we go assuming we know what’s best for the people who live there, or are we ready to listen, to be patient, to learn? Do we go with unbending ideas, or are we willing to allow our views to be shaped by the people we encounter who have stories of their own and perfectly logical reasons for living the way they do?

4. Is our help actually helpful? I mean, really, is it their number one priority for us to paint their church building for the fifteenth time?

5. Once we return, how do we debrief? Do we focus on how we feel, on how good our pictures on Facebook are, and on how “blessed” we were? Do we reflect on what the lavish hospitality of our hosts cost them? Do we consider what might have been gained and lost by the community because of our visit?

Don’t get me wrong: there are good reasons for going to spend time among the poor and there are good ways of doing so. It’s possible to do it well, thanks be to God. But it’s also possible to have bad reasons and bad ways of going. We may never be 100% sure of our motives, and we may never be truly able to see our visit through the eyes of our hosts, but it seems we ought to try.

It seems we ought to do better than wannabe revolutionaries.