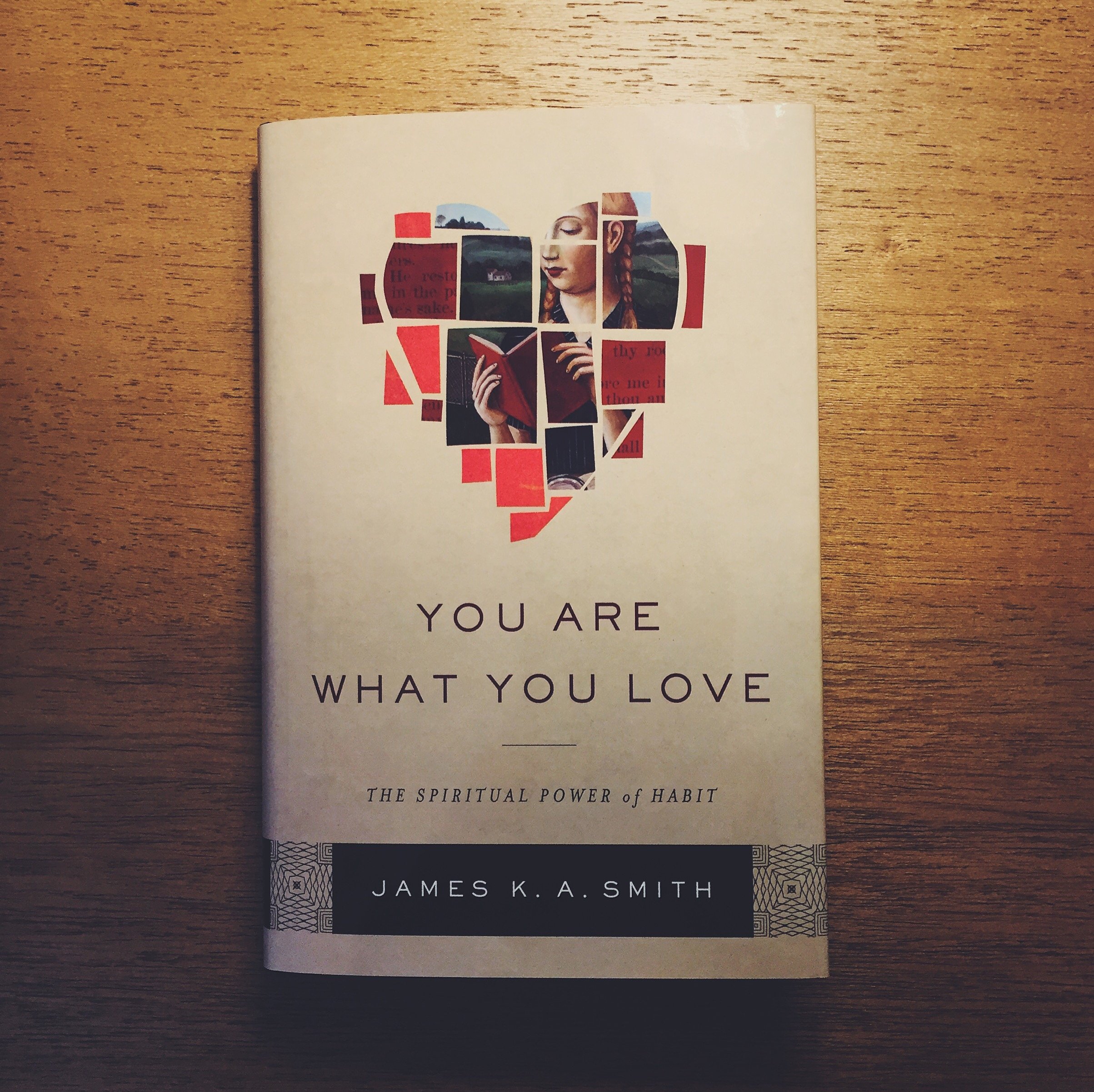

You Are What You Love

In the acknowledgements in the final pages of James K.A. Smith’s You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit, there’s a telling paragraph in which Smith says that he wrote this book “thanks to the prompting of two liturgical theologians” – one of whom is the late Robert Webber.

“Robert Webber’s work had a significant impact on me at a crucial phase of my life, and in many ways I’m simply writing in his wake,” Smith says. “This little book is a dinghy bobbing along behind the ship of Webber’s ‘ancient-future’ corpus. If I can help a few people board the mother ship, my work here is done.”

Webber’s work was influential in my own life too, especially a few years ago as I laced up my boots to walk the Canterbury Trail. The other author who was instrumental in my joining the Anglican Communion was Smith, a Dutch Reformed philosopher (though maybe not a stereotypical one) who teaches at Calvin College.

I read his book Desiring the Kingdom four summers ago on the recommendation of some friends, and it was simultaneously a slog and a joyride. Though my head was spinning most of the time (to say nothing of my heart), I resonated deeply with Smith’s claim that “liturgies – whether ‘sacred’ or ‘secular’ – shape and constitute our identities by forming our most fundamental desires and our most basic attunement to the world.” Though I couldn’t grasp all the implications then (or, really, now!), nonetheless I sensed this to be true: “Liturgies make us certain kinds of people, and what defines us is what we love.”

You are what you love.

We humans fancy ourselves completely rational creatures. And as Christians, especially in the West, we tend to equate spiritual maturity with the accumulation of right ideas. But our logical grasp of “facts” only takes us so far.

God has given us the gift of intellect, true. And yes, belief is essential. But before we are rational creatures, we are liturgical, desiring creatures – driven and compelled by what we love. Advertisers know who we really are. So do sports executives and savvy politicians.

You are what you love.

So if liturgies – whether “sacred” or “secular” – are how our loves are formed, we had better hitch our hearts to good liturgies. For me, the implications of that idea were far-reaching. But for one thing, being at an ecclesial crossroads at the time, it meant becoming part of a church (1) that intuitively got that we are liturgical creatures and (2) that was committed to drawing upon the liturgical riches of the Christian church across time and space.

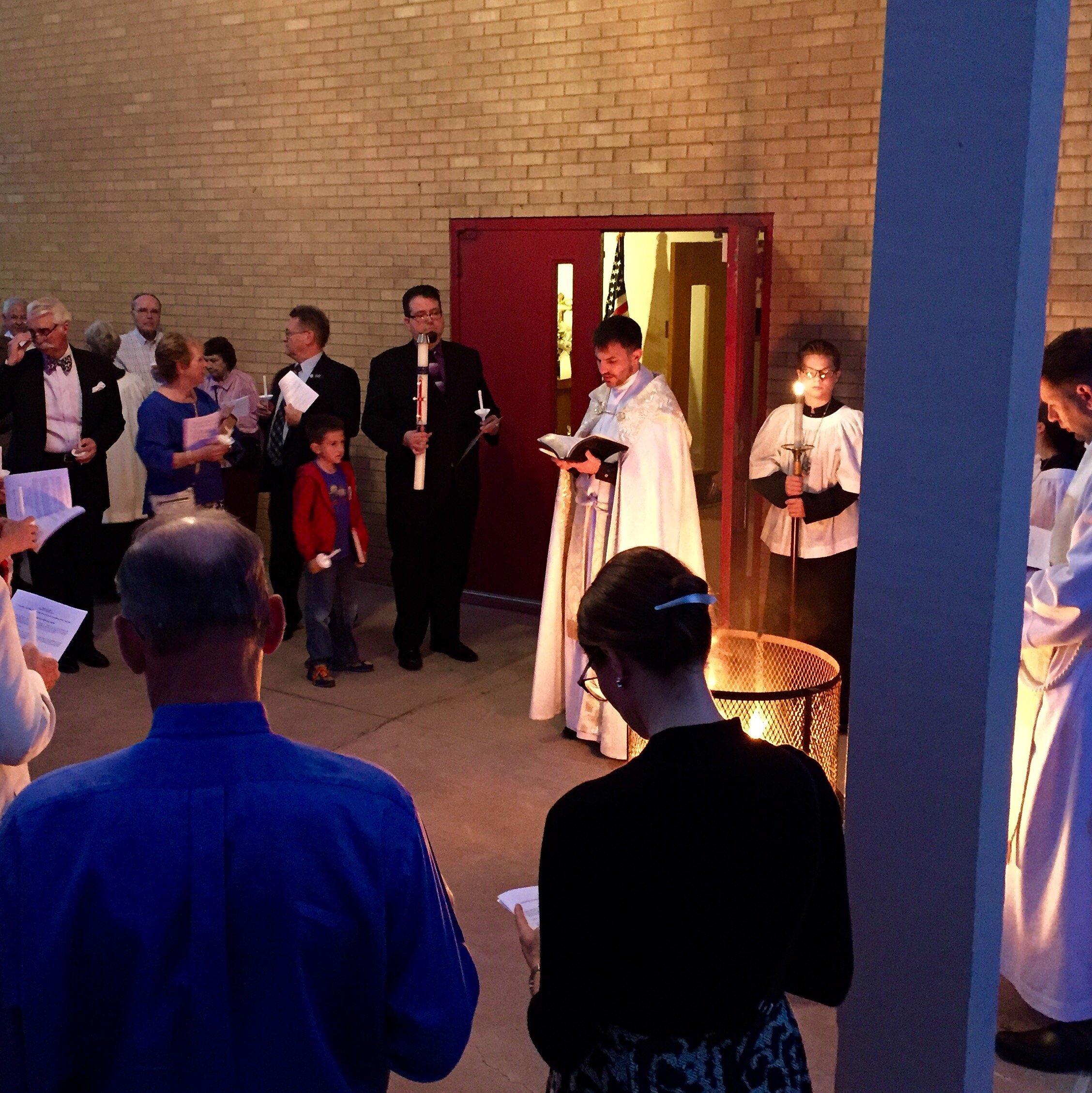

The first Sunday at our Anglican church here in Phoenix felt to me like a homecoming, and over the past two and a half years, it’s been a good home to us. It has also, to be honest, felt a bit like being an expat in a foreign land: even still we’re learning a new culture, complete with confusing language patterns, vastly different forms of dress, and a whole slew of unspoken assumptions.

But that’s okay. Little by little we’re learning the language. Little by little we’re picking up on those assumptions. Little by little, over the course of the liturgical year, the vestments have come to take on new meaning. We’re becoming acculturated, not just because we read books or listened to lectures, but because we’ve participated, week after week, month after month, year after year.

That’s the power of habit. But it goes deeper than merely picking up on cultural cues. Much deeper. It is starting to seep into us where it counts. As Smith writes, “The drama of redemption told in the Scriptures is enacted in worship in a way that makes it ‘sticky.’ Study and memorization are important, but there is a unique, imagination-forming power in the communal, repeated, and poetic cadences of historic Christian worship.”

Every Sunday morning (and yes, in quiet times throughout the week using the Book of Common Prayer), we’re guided through the narrative arc of Scripture. We praise God for his goodness and glory. We invite Jesus to be in our midst. We hear readings from the Psalms, the Old Testament, an Epistle, and one of the four Gospels – all tied together by some common thread. We hear a sermon. We recite the Creed. We pray “for the whole state of Christ’s Church and the world.” We confess our sins. We are reminded that we are forgiven, and in turn, we pass the peace to our reconciled brothers and sisters in the pews. We come to the communion table, trusting not in ourselves, but in the “abundant and great mercies” of Christ. We eat the bread and drink the wine. Then we thank God for feeding us. And, nourished, we are sent back into the world to do the work God has given us to do.

Each Sunday morning we sit, stand, kneel, and turn. Some of us make the sign of the cross or genuflect as a sign of reverence. We sing, we speak, we listen. We eat, we drink, we pray. We go. Some weeks we’re distracted, tired, or desperate. Some weeks our hearts are filled with joy. But we gather as fully embodied beings, walking through the same liturgy together, bearing one another’s burdens, sharing in one another’s joys – all the while being invited into the life of the body of Christ.

Make no mistake: the liturgy I’m describing is no silver bullet. It’s something better than that. Little by little, slowly but surely, the Spirit is using it to form us, to reorient us – we whose hearts have been pointed toward all manner of lesser loves.

No book is enough to shape our loves. You’ll need time-tested, Spirit-filled, life-giving habits to do that. But a book can open the door to new worlds to explore, and what I’m trying to say here is that Jamie Smith’s books have helped to do that for me. And while the profound insights of Desiring The Kingdom and Imagining The Kingdom were a bit out of reach for many of us, in You Are What You Love Smith has made them wonderfully and winsomely accessible – amazingly, without losing any of the depth.

I’m not particularly interested in convincing people to become Anglican – God knows we’ve got our fair share of problems! But I will be recommending You Are What You Love widely and often. Consider yourself forewarned.